A closer look at California's $267 million war on "organized retail crime"

On Tuesday, California Governor Gavin Newsom (D) announced the state would spend hundreds of millions of dollars to combat "organized retail crime." More than $267 million will be distributed in grants to 55 cities and counties across the state. Individual police departments will receive cash infusions of up to $23 million.

"Enough with these brazen smash-and-grabs," Newsom said. "With an unprecedented $267 million investment, Californians will soon see more takedowns, more police, more arrests, and more felony prosecutions. When shameless criminals walk out of stores with stolen goods, they’ll walk straight into jail cells."

But one thing that was missing from Newsom's announcement was any data on the scope of organized retail crime in California. How much merchandise is stolen in California by organized retail crime rings? Is the amount of organized retail crime in California increasing rapidly?

Popular Information contacted the California Retailers Association for data on organized retail crime in the state. A representative of the Association replied, "we do not have data." In a follow-up interview, California Retailers Association president Rachel Michelin told Popular Information that her organization determined that organized retail theft was a "growing" problem in California based on conversations with major retailers, small businesses, and law enforcement.

The president of the Retail Industry Leaders Association (RILA), Brian Dodge, appeared on Fox News and said that organized retail crime was "particularly acute" in California. In response to a request for data to back up Dodge's claim, a spokesperson for the RILA said that organized retail crime was a "significant problem in CA" but did not provide any data.

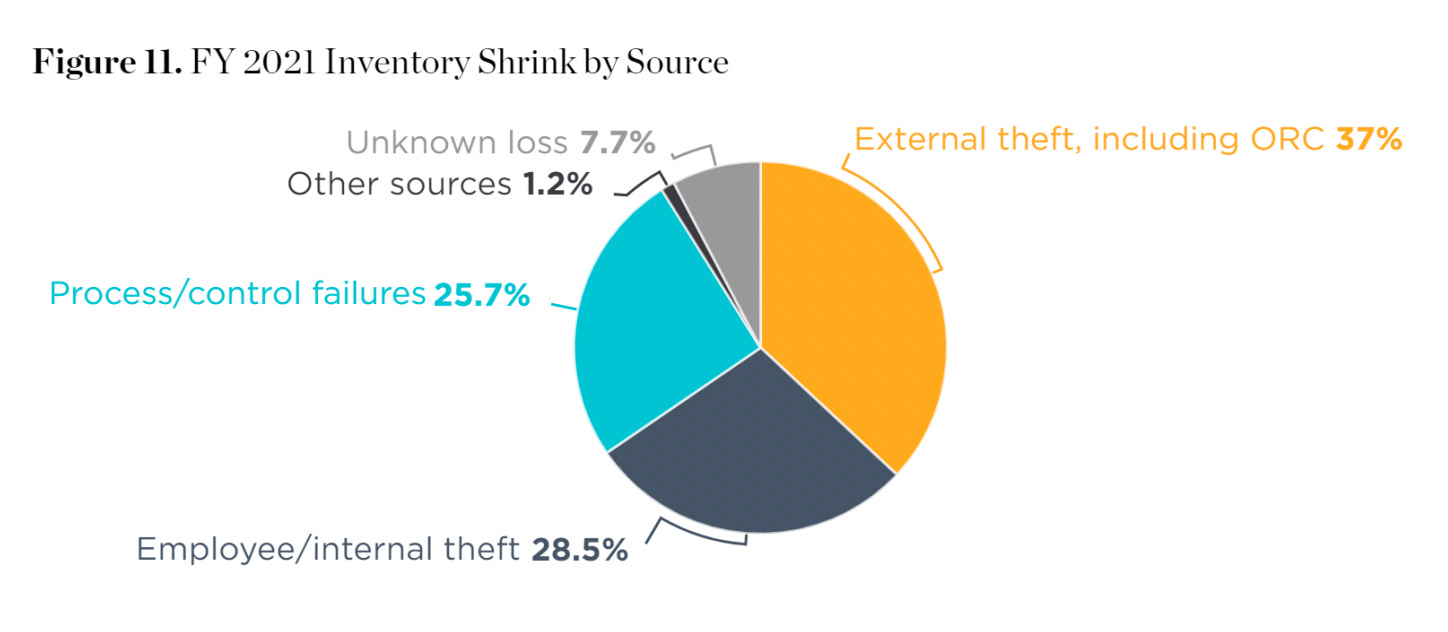

Retailers and their lobbyists like to talk about the problem of organized retail crime but are less eager to quantify it. In May, the National Retail Federation (NRF) told Popular Information that it "does not have estimates specific to ORC [organized retail crime]." Instead, the NRF talks about "shrink," an industry term that refers to missing inventory. According to the NRF, over half of shrink is due to employee theft and internal control failures. 38% of shrink is due to "external theft," a category that includes both run-of-the-mill shoplifting and organized retail crime.

If organized retail crime is driving a surge in shrink nationally, it's not showing up in the data. In 2021, the latest data published by the NRF, total shrink was 1.4% of sales. That was down from 1.6% of sales in 2020. Total shrink has been hovering around 1.4% for more than a decade.

Notably, as recently as 2020, the NRF provided estimates for organized retail crime. The NRF estimated organized retail theft "costs retailers an average of $719,548 per $1 billion dollars in sales." That means about 0.07% of sales, or 5% of total retail shrink, is attributable to organized retail crime.

So, organized retail crime does not appear to be a crisis nationally. But perhaps California is an outlier? California has had a series of high-profile "flash mob" burglaries. In Los Angeles, for example, large groups robbed a string of upscale stores this year, including Nordstrom, Yves Saint Laurent, Gucci, Nike, and Versace.

State crime data in California, like most states, does not break out "organized retail crime." But between 2017 and 2022, shoplifting in California declined by 10.5%. Shoplifting cratered in 2020 and 2021 during the pandemic. Shoplifting in California has since rebounded somewhat but still is well below pre-pandemic levels. Similarly, burglary in California — a category that would include "smash-and-grab" organized retail theft — declined by 17.6% between 2017 and 2022. The burglary rate is a small fraction of what it was a few decades ago. In 1993, for example, the burglary rate in California was 1,303 per 100,000 people. In 2022, it was 368 per 100,000 people.

Statewide data, however, is only available through 2022. Maybe the problem of organized retail crime started this year?

2023 data from most major California cities, however, does not reflect a significant increase in shoplifting or organized retail crime. In San Francisco, larceny-theft, which includes shoplifting, is down 5.6% year-to-date. Burglary in San Francisco is down 6.8% year-to-date. In San Jose, burglary and larceny are both down nearly 20% year-to-date. In Los Angeles, burglary has decreased 2.7% year-to-date, but theft has increased 14.1% year-to-date.

Taken as a whole, the available data suggests organized retail crime does not appear to be a growing problem in the nation or California. So is combating organized retail crime the best use of $267 million in taxpayer dollars?

California's $2 billion wage theft problem

Corporate trade groups do not appear eager to estimate the scope of organized retail crime in California. But it is possible to come up with a rough estimate. The NRF self-reported a total of $94.5 billion in shrink in 2021, the last year data is available. According to the NRF's 2020 estimate, about 5% of total shrink is attributable to organized retail crime. That means that, nationally, organized retail crime is responsible for about $4.73 billion in lost merchandise. California accounts for about 14.5% of the national economy. So, according to the industry's own rough estimates, organized retail crime could be a $686 million problem in California.

Wage theft in California, the amount of money employers steal from their employees, is estimated to be $2 billion dollars a year. So wage theft is about three times as large a problem in California than organized retail theft. Moreover, the victims of organized retail theft are corporations that, despite theft and other causes of shrink, are highly profitable. The victims of wage theft are low-wage workers struggling to make ends meet.

Could California use more resources to identify and prosecute wage theft? The answer is, unequivocally, yes. In March, the Los Angeles Times reported, "workers robbed of pay currently must wait an average 780 days to have their cases heard." Victims of wage theft have to wait more than two years to have their claims adjudicated even though "[b]y law those hearings are to be held in 120 days."

Workers who are successful are generally awarded a small fraction of what they claim to be owed, and "most workers are unable to collect their owed wages even when winning awards." The state Labor Commissioner’s wage theft unit, which is responsible for hearing wage theft claims, "has blamed staffing shortages for long delays in hearing cases." Labor advocates are pushing for a "streamlined hiring process" and "increased pay" to fill the unit's many vacancies.

Will more aggressive policing and prosecution reduce organized retail crime?

Newsom is spending $276 million to take a "tough on crime" approach to retail theft.

But will "more police," "more arrests," "more takedowns," and more aggressive prosecution really make a difference? It's far from certain. Most shoplifters are not making a calculation about the potential legal consequences. Spending $267 million in an effort to put a few more people behind bars is probably good politics. But, without addressing the root issues the drive people to a life of crime and desperation, it may exacerbate the problem over the long run.

Newsom walked right into the classic Fox News trifecta of 1) 'lawlessness', associated with 2) anti-business sentiment, taking place in 3) California. He could spend $20B and he won't satisfy the outrage machine (because it can't be) while destroying lives and wasting tax-payer money in the process.

Thanks Judd and Rebecca, someone has to inform Gavin Newsome about what's going on regarding this issue. I'm sure that the governor knows and hears from corporate owners and those who own high end stores, but that he's not likely to hear from the low wage workers who suffer deeply when their low wages are withheld. If WAGE THEFT in CA creates a $2 billion dollar problem, 3 times the amount caused by regular theft and organized retail theft, how can this more serious problem be addressed? I'm shuddering at the prospect of more police, more people in prison, and simply more suffering by those who have no voice.