An extraordinarily important legal decision just dropped, and no one is talking about it

On February 13, 2020, Nicholas Robertson was shot in Jackson, Mississippi. Wounded, Robertson knocked on the door of a nearby home. But by the time the police arrived, Robertson was unresponsive and died before he could be transported to a hospital.

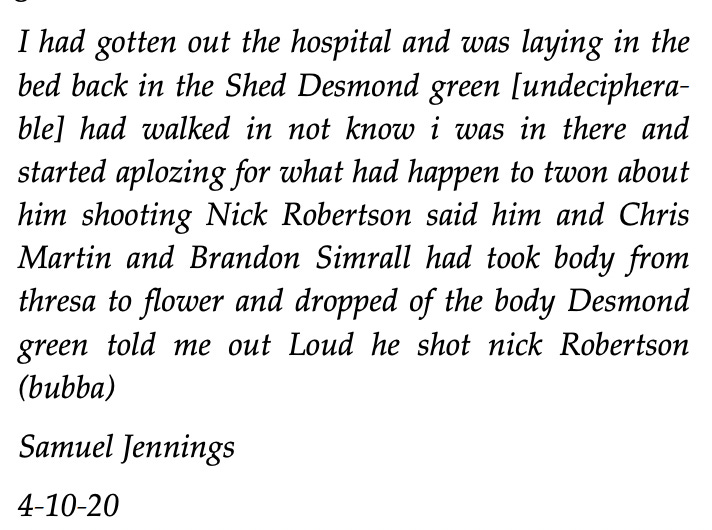

Two months later, in an unrelated incident, Samuel Jennings was arrested for burglary and grand larceny. Jackson Police Department Detective Jacquelyn Thomas visited Jennings at the detention center. Jennings provided Thomas with a rambling written statement pinning the blame for Robertson's murder on a man named Desmond Green. The statement also claimed that Green moved Robertson's body after the murder:

Thomas used this uncorroborated statement to convince a grand jury to indict Green for murder. For 22 months, Green was held in a jail "full of violence, rodents, and moldy food." According to Green, he "often did not have a mattress, or even a pad, to sleep on." Green said he "constantly feared for his life."

But Green was indicted on a lie.

Jennings recanted his story in March 2022. Jennings said that when he made the statement, he was high on meth and provided the written statement to Thomas "to help myself get out of jail." Green had never confessed, Jennings admitted. Damningly, Jennings said that Thomas presented him with a photo lineup of suspects, and Jennings initially picked "Photo 1." But, according to Jennings, Thomas "pointed to the 5th photo of [the] lineup," and Jennings changed his selection.

Green was finally released from jail on April 21, 2022.

In February 2023, Green sued Thomas, alleging that the detective violated his Constitutional rights under the Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments. (Green also sued the City of Jackson and Hinds County, which operated the detention center where Green was incarcerated.)

Thomas sought to have Green's lawsuit against her dismissed, citing the doctrine of qualified immunity. A federal judge, Carlton Reeves, rejected Thomas' motion on Monday.

It has received scant media attention, but it is a very big deal. In a decision praised by legal scholars for its "power and beauty," Reeves establishes why the doctrine of qualified immunity, which can protect law enforcement officials sued for misconduct, is "unsupportable as a matter of history, text, and policy." Reeves calls on the Supreme Court to acknowledge its mistake and eliminate the doctrine of qualified immunity entirely.

What is qualified immunity?

After the Civil War, "white supremacists unleashed waves of terrorism across the South." They were able to act with impunity because, in many cases, "judges, politicians, and law enforcement officers were fellow Klansmen and loyal sympathizers." In response, Congress passed the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871. The Ku Klux Klan Act imposes liability upon any person who, acting under color of state law, deprives another of a federal right.

The text of the Ku Klux Klan Act had no exceptions or immunities. And, for many decades, the courts simply enforced the law and imposed civil penalties on law enforcement officers who violated the constitutional rights of another person.

That all changed in 1967 when the Supreme Court considered Pierson v. Ray. The case involved Black ministers who were arrested for entering a "Whites Only" bus terminal waiting room. The ministers beat the criminal charges in court and then sued the police officers who arrested them, arguing their constitutional rights were violated.

The Supreme Court decided that the officers were entitled to "qualified immunity" because they had a good faith belief that they needed to arrest the ministers to prevent violence. The police officers actually "had no proof that the ministers were a threat to public safety." In reality, there was a crowd of about 30 bystanders "threatening violence" against the ministers.

In ruling against the ministers, however, the Supreme Court "took a law meant to protect freed people exercising their federal rights in Southern states after the Civil War" and flipped it on its head. In creating the doctrine of qualified immunity, the Supreme Court began using the Ku Klux Klan Act to protect southern law enforcement officers still violating the constitutional rights of Black Americans 100 years after the Civil War.

Almost 60 years later, qualified immunity "protects public officials from liability for civil damages insofar as their conduct does not violate clearly established statutory or constitutional rights of which a reasonable person would have known." What does it mean for a right to be "clearly established?” Courts have found that a clearly established right "is one that is sufficiently clear that every reasonable official would have understood that what he is doing violates that right." Put another way, qualified immunity "protects all but the plainly incompetent or those who knowingly violate the law."

In practice, qualified immunity has given a free pass to law enforcement officers who engaged in egregious violations of Constitutional rights. Here are a few examples cited by Reeves in his decision:

Courts let correctional officers spray some chemical agent in a person's face “for no reason at all,” because it was only clearly established that guards could not use “the full can of spray.” McCoy v. Alam (2020)

Courts let police officers who were inside a car kill a person who didn't warrant lethal force. The law clearly established only that an officer could not shoot a person from outside a car. Stewart v. City of Euclid, Ohio (2020).

A court let five police officers shoot a man 22 times as he lay motionless on the ground, after tasing him four times, kicking him, and placing him in a chokehold. It was not clearly established that officers could not shoot a motionless person who possessed a knife. Estate of Jones v. City of Martinsburg (2018).

Courts let a correctional officer watch a suicidal detainee strangle himself to death with a telephone cord, after officials placed him in the cell, with the cord, knowing he was unstable and had repeatedly attempted suicide. It was not clearly established that correctional officers who watch a person attempt suicide had to “call for emergency medical assistance.” Cope v. Cogdill (2021).

Effectively, qualified immunity allows "government agents are at liberty to violate your constitutional rights as long as they do so in a novel way."

A Reuters investigation in 2020 found that, between 2015 and 2019, more than half the time police officers are sued for using excessive force, appellate courts dismiss the suit on the basis of qualified immunity. Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor argues that the doctrine of qualified immunity has increasingly become an "absolute shield" for police officers' misconduct.

Judge Reeves' landmark decision

Reeves found that using the Supreme Court's existing standard, Thomas is not protected by qualified immunity. Moreover, Reeves ruled that the doctrine of qualified immunity itself is legally unsound and should be discarded. Qualified immunity does not appear in the Ku Klux Klan Act or the Constitution. Reeves argues that if Congress wanted to give law enforcement officers qualified immunity, it could pass legislation. But Congress chose not to do so.

The Supreme Court has created legal doctrines that are necessary to "give life and substance" to the rights delineated by the Bill of Rights, Reeves notes. Qualified immunity, however, has the opposite effect. It takes rights guaranteed by the Constitution and renders them null and void.

Since 1967, the Supreme Court has expanded qualified immunity, making it increasingly difficult to hold law enforcement officers accountable for misconduct. In 1999, one could prove that a Constitutional right was "clearly established" in a given circumstance by “a consensus of cases.” But in 2011, the Supreme Court upped the threshold to a "robust consensus of cases."

The most compelling reason to leave qualified immunity in place is the doctrine of stare decisis. Under this theory, since qualified immunity has been established precedent, law enforcement officers have grown to rely on it. Therefore, the Supreme Court should be hesitant to eliminate it.

But Reeves argues that the Supreme Court's decision in Dobbs, upending "50 years of precedent" and eliminating "the Constitutional right to a pre-viability abortion," negates this concern. In Dobbs, opponents of abortion rights argued that the Supreme Court, in recognizing abortion rights, had “short-circuited the democratic process” and “necessarily declared a winning side” in a long-running social controversy.

Reeves notes that the case for eliminating qualified immunity is stronger than the case for eliminating abortion rights. In Roe, the Supreme Court created a Constitutional framework around an issue where Congress had not acted. In Pierson, the Supreme Court created qualified immunity and negated a standard explicitly established by Congress with the Ku Klux Klan Act. It should be much easier, Reeves says, for the Supreme Court to conclude that Pierson was "egregiously wrong from the day it was decided."

The Supreme Court has justified qualified immunity on a policy basis, arguing that it is necessary to protect government officials from "the expenses of litigation, the diversion of official energy from pressing public issues, and the deterrence of able citizens from acceptance of public office." But, as Reeves notes, emergency room physicians also play a critical role and the courts have not created qualified immunity for their negligence. The same goes for other critical sectors like utilities and the financial industry. Only government officials, including law enforcement officers, have been awarded qualified immunity by the courts.

UCLA Law Professor Joanna C. Schwartz argues that the concept of qualified immunity for law enforcement based on "clearly established statutory or constitutional rights" is incoherent. Courts base these decisions on previous cases, but police officers "could never learn the facts and holdings of the hundreds or thousands of cases that clearly establish the law and, even if they learned about some of these cases, they would not reliably recall their facts and holdings while doing their jobs."

Reeves concludes that "[j]udicial supremacy has too-often deprived the People of their proper role in deciding constitutional torts brought under the Ku Klux Klan Act." As an alternative, he proposes trusting juries to make judgments as to whether the conduct of law enforcement officers violates the Constitution. Jurors, Reeves says, understand that law enforcement officers sometimes "make split-second judgments—in circumstances that are tense, uncertain, and rapidly evolving.” And jurors also understand how to distinguish those incidents from "a pattern of misconduct" or an "act in a calculated fashion.”

An excellent series of arguments against "qualified immunity!"

There is a lot of negative stuff being repeated incessantly by our increasingly obtuse media AND there are also silver linings hiding in the weeds, which makes them very hard to see unless one is looking or soomeone else is looking out.

Bravo Judge Carlton Reeves! Bravo indeed!

Thank you Judd Legum. Good looking out!

It’s reports like this that keep me reading your work. You keep pointing out important things that otherwise would go unnoticed. Thank you.