GameStop revisited

In January, everyone was talking about GameStop. The video game retailer's stock skyrocketed from just over $3 in early 2020 to over $350 in January 2021. The rise was driven, in large part, by small investors who communicated on a Reddit forum called r/wallstreetbets. Many of these investors used no-cost trading apps like Robinhood to acquire shares of GameStop and other so-called "meme" stocks.

Some of those investors were fans of Ryan Cohen, the former Chewy CEO and current GameStop board member. Cohen believed that GameStop, which is known for its brick-and-mortar stores, could be reimagined as a force in online retailing. Some of those investors just wanted in on the fun. And other investors wanted to stick it to hedge funds that had been aggressively shorting GameStop.

To execute a short sell of a share of GameStop (or any stock) an investor borrows it from someone else and immediately sell it. The hope is that the short-seller can repurchase the stock later at a lower price. The drop in share price becomes profit for the short-seller.

Short sales can be very profitable, but they are also very risky. If an investor purchases a stock for $50 and the stock price collapses, the most the investor can lose is $50. But when an investor executes a short sale for a stock at $50 and the stock price increases to $350, it costs $300 to close out the position.

One of the hedge fund managers who aggressively shorted GameStop stock was Gabe Plotkin, who runs Melvin Capital Management. Plotkin started the fund in 2014, manages $12 billion, and averaged returns of 30% per year. But Plotkin bet big against GameStop. The run-up in GameStop shares caused the value of Plotkin's fund to shed 15% of its value — $1.8 billion — in the first three weeks of 2021. And things were rapidly getting worse.

Plotkin needed a bailout from two other hedge fund titans, Steve Cohen and Ken Griffin. They rescued Plotkin with a $2.75 billion cash infusion. But that meant Griffin, who runs Citadel LLC, also had a significant financial interest in Plotkin successfully unwinding his position in GameStop.

This is where things get controversial. One of Citadel's activities is to serve as a "market maker" for companies like Robinhood. Essentially, Citadel matches people who want to buy stock on Robinhood with sellers. Citadel pays Robinhood for the right to Robinhood's "order flow." Robinhood makes hundreds of millions of dollars annually selling its order flow.

Selling order flow is Robinhood's primary source of revenue. (Trades on Robinhood are free.) Citadel paid Robinhood $142 million in the first quarter of 2021, which was 43% of Robinhood's total revenue. Citadel, in turn, profits from the "spread" — the small difference between the price to buy and sell a stock.

In many ways, companies like Citadel are Robinhood's real "customers." The people who use the Robinhood app are the product.

That's why when Robinhood and other retail brokers prohibited its users from buying GameStop on January 28, causing GameStop's stock price to fall, many people were very angry. Was trading in GameStop restricted to protect the interests of hedge funds like Citadel?

Both Robinhood and Citadel vociferously deny that anything inappropriate transpired. Robinhood says it was forced to restrict the trading of GameStop stock because of demands for billions in cash by National Securities Clearing Corporation (NSCC). Stocks trades don't formally complete for a couple of days. In the interim, the NSCC requires brokers to put up cash to guarantee the trades while the transaction finalizes. This amount, known as margin, goes up when stocks are highly volatile.

Griffin, in Congressional testimony last February, said that he "had no role in Robinhood’s decision to limit trading in GameStop or any other of the ‘meme’ stocks." Citadel, in a statement, said the company "has not instructed or otherwise caused any brokerage firm to stop, suspend, or limit trading or otherwise refuse to do business." More recently, Griffin said “the GameStop conspiracy theory” was like "a bad comedy joke."

But internal communications recently made public as part of a class-action lawsuit against Robinhood, Citadel and other firms involved in the controversy have cast some doubt over these denials.

The internal communications

The amended complaint of the class-action lawsuit, known as In Re January 2021 Short Squeeze Litigation, alleges that on "January 27, 2021, the day before the restrictions were implemented, high-level employees of Citadel Securities and Robinhood had numerous communications with each other that indicate that Citadel applied pressure on Robinhood."

In an internal Slack message that day, Robinhood's Chief Operating Officer, Gretchen Howard, tells Robinhood CEO Vlad Tenev that she and two other Robinhood executives (Dan Gallagher, Robinhood's Chief Legal Officer, and Jim Swartwout, President of Robinhood Securities) will be speaking with Citadel at 5 PM. Howard says she believes that Citadel will make "some demands" related to reducing payments for order flow (PFOF).

Tenev appears concerned. He responds by asking Howard to try to set up a "chat" between Tenev and Griffin.

A couple of hours later, Robinhood's Senior Director of Clearing Operations, whose name was redacted, tells Jim Swartwout that he believed several "real large" firms were having "really bad nights." Swartwout, who was on the 5PM call with Citadel, tells the employee "everyone is," adding "you wouldn't believe the convo with Citadel. Total mess."

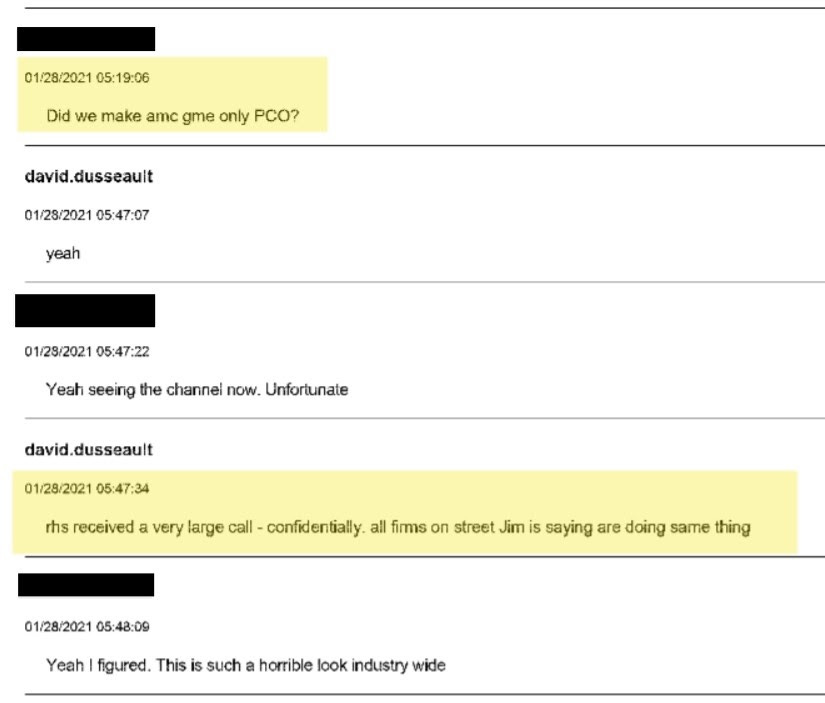

Messages sent on January 28 suggest that there was coordination among brokers to limit trading on GameStop stock at the same time. David Dusseault, President of Robinhood Financial, says Robinhood Securities received "a very large call–confidentially" and Swartwout confirms that all firms are "doing [the] same thing."

A Robinhood employee, whose name has been redacted, replies that it was "a horrible look industry wide."

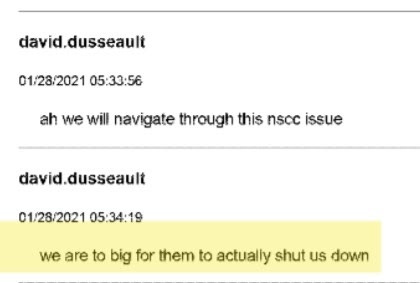

Other messages suggest that Robinhood was not as concerned about demands for increased margin from NSCC. Robinhood had met the latest demand for margin by the time the markets opened on January 28. Later that day, Dusseault, responding to inquires about the NSCC says he believed that Robinhood was "too big" for NSCC to shut down.

None of this necessarily proves that Griffin, Robinhood, or Citadel lied. But Ben Hunt, a former hedge fund manager who now writes the newsletter Epsilon Theory, offers this interpretation:

Epsilon Theory’s Hunt says he doesn’t believe Griffin lied. Rather, he says, he thinks the messages imply that “Citadel was saying, ‘We are not going to pay for order flow on GameStop,’ at which point Robinhood then did things. Do I suspect that [Citadel] understood there would be significant consequences for that? Yes. Is that the same thing as saying, ‘You need to stop trading in GameStop’? No, it’s not.”

If Hunt's theory is correct, it reflects the reality of the financial world. Elite operators know how to bend the rules to get what they want without suffering any consequences. Typical investors, meanwhile, end up holding the bag.

Thanks Judd for making a complicated subject a little more human-sized. Hard to know just what changes might have prevented this from happening - fwiw Reddit has made some changes, seems more proactive re spreading of Covid misinformation, but doesn’t really seem amenable/easily adaptable to investor protection. Caveat emptor, as usual.

Some reg folks made money on this. But the 1% with big bucks control the game. Every game. Not just financial markets.

Bannon said he wanted tear everything down and start a new world order. Should be interesting to see if the 1% money rescues him.

I know my grocery bill has gone haywire in the past few months and my gasoline bill makes my BP go up. Question to ponder...The regular guy feels the pinch in all of these "experiments" like Robinhood/Gamestop. The trickle down of the 1% losing money reappears as a hand in our wallets, methinks.