The positive power of partisanship

Welcome to the free weekly edition of Popular Information -- written by me, Judd Legum.

If you enjoy reading Popular Information, you can get four newsletters every week with a paid subscription. It's $6 a month or $50 for an entire year.

This is ad-free, independent media. To make it work, I count on readers like you.

I'm also offering a Founding Membership. For $150, you'll get an annual subscription, and I'll give away four subscriptions to people who otherwise may not be able to afford it.

If you have any questions, email me at judd@popular.info.

My friend Walt Hickey writes an excellent newsletter called Numlock that focuses on the numbers in the news. It's a quick read, and I learn something new from it every time. You can subscribe HERE.

The positive power of partisanship

"When bad men combine, the good must associate; else they will fall, one by one, an unpitied sacrifice in a contemptible struggle." — Edmund Burke

One thing Americans can agree on is that Americans are too disagreeable. Our partisan divisions, we are told, are an acute threat to our democracy.

"[M]embers of the self-declared resistance are tearing America apart because the election didn't go their way," Michael Goodwin, a pro-Trump columnist for the New York Post, opined in October -- an argument echoed by Sean Hannity and many others on the right.

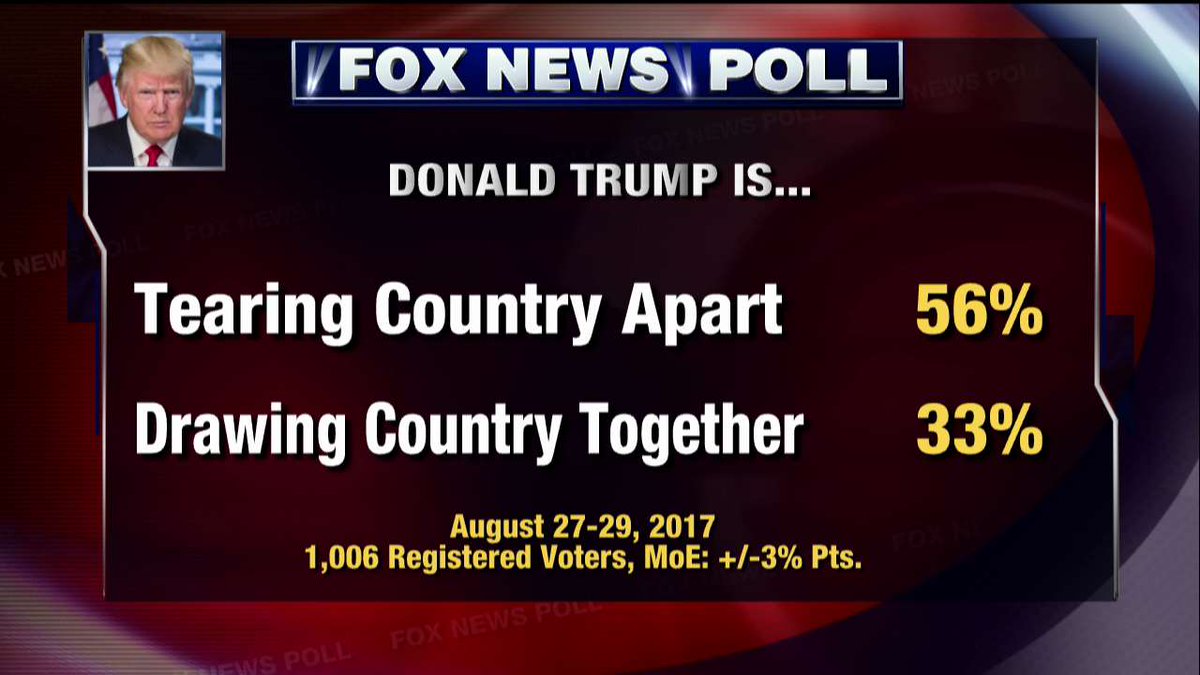

Meanwhile, nearly six in ten Americans believe Trump is "tearing the country apart."

Arnold Schwarzenegger, the former Governor of California, blames both sides. "The politics of division and anger and resentment can drive a strong base to the polls, yes. But it is tearing our country apart at the seams," the Governator said.

According to the centrists who grace the nation's prestigious op-ed pages, the solution is to cast aside our partisan divisions and seek compromise. The problem with politics, David Brooks explained in a 2014 column, is that people care too much.

The problem is that hyper-moralization destroys politics. Most of the time, politics is a battle between competing interests or an attempt to balance partial truths. But in this fervent state, it turns into a Manichaean struggle of light and darkness. To compromise is to betray your very identity.

This is deeply misguided.

Disagreement and partisanship are essential components of a vibrant democracy. Muting criticism and debate is a feature of totalitarian regimes.

This is not to say that America's political system does not have problems. But the solution is not less partisanship; it's better partisanship.

Partisans make democracy work

In a democracy, progress requires a large group of people to come together around a set of common goals. This is the function of parties and partisans.

Party affiliation itself requires compromise. Partisans share a basic set of core beliefs but individuals, particularly those running for office, are willing to curtail or amend their beliefs to attract others to the group.

This is a balancing act. There is a limit to how much individuals are willing to compromise their personal views to achieve the party's larger goals. Defining these limits is often the source of intraparty disputes, which are also a healthy part of a functioning democracy.

Major policy requires partisans

Major policy initiatives -- the kind that can change people's lives for the better -- require a durable political coalition.

Take Obamacare, for example. It was signed into law in 2010. But its core features did not get implemented until 2014. It contains pilot programs to curb costs that won't be completed for another decade.

For Obamacare to have a chance at success, it needs a loyal group of partisans to defend it. The defenders of Obamacare are not blind to facts. But they are believers in the cause and exhibit loyalty and patience.

In American democracy, all of the House and one-third of the Senate is up for election every two years. The decision-makers change. The linkage of loyalty to party gives ambitious policies a chance to succeed.

The nonpartisan alternative

The alternative to partisanship is to pursue ad hoc, nonpartisan compromises around individual policies. This avenue seems more intellectually honest and rigorous. Russell Muirhead explains the appeal in his book, The Promise of Party in a Polarized Age:

Independence often seems a more admirable political posture than partisanship. Ideally, citizens should be impartial, like judges, and objective, like scientists. They should make up their minds based on facts, not longstanding loyalties.

But an independent approach has its limitations. It's no surprise that advocates of this approach promote a version of politics that is about making small changes to the status quo.

David Brooks, in a column called "Why Partyism Is Wrong," offers this description of what's at stake:

[P]olitical campaigns and media provocateurs build loyalty by spreading the message that electoral disputes are not about whether the top tax rate will be 36 percent or 39 percent, but are about the existential fabric of life itself.

It's true that if you believe elections should be about deciding whether the top tax rate is 36 percent or 39 percent, partisanship has little value. This is fine if you believe, in general, that the status quo is good. You don't need partisans to work around the margins.

In this way, nonpartisanship functions as a smart way for certain kinds of conservatives to advance their beliefs while seeming open-minded. They may have convinced themselves that they support a nonpartisan version of politics because they want to heal America's divisions. But they are comfortable with nonpartisanship because they are comfortable with how things stand in America.

But if you believe, on the other hand, that it is wrong that virtually all economic gains in the last 40 years have been captured by the top 10%, you require a different, more partisan, approach.

You can't resolve political problems through reason and evidence alone, because a big part of the political debate is determining what constitutes a problem to be solved. Even if there is an agreement on the definition of the problem, it needs to be prioritized against all other problems. Disputes about these fundamental questions can be messy and divisive. But they are also necessary.

Good partisanship

Partisanship gets a bad rap. It is a term that is generally used to describe those who have blinded themselves to reality. Some partisans are like that. But it doesn't have to be that way.

Good partisanship is like a good friendship. A good friend is loyal and supportive. Good friends unite around common values or interests. A friend would not abandon you over small things, like showing up late to a movie. When you need help, a friend is there for you, even if it is inconvenient.

But friendship is not blind allegiance. If your friend steals your car, you may decide not to be friends anymore.

Good partisans exhibit the same traits of loyalty and patience as good friends. But if problems arise, a good partisan does not stay silent. If things get bad enough, a good partisan will sever ties with the party.

Bad partisanship

Partisanship is not always a virtue. Good partisans unite around values and interests. Bad partisans unite around hatred and a distorted view of reality.

The problem with Trump is not that he's uniting a large group of people around an agenda. It's that the agenda is not based on values and defensible facts but bigotry and misinformation.

Six months after he was elected, 58% of Republicans believed Obama was not born in the United States, despite incontrovertible evidence disproving the claim. Trump used that shared belief to launch his political career.

That is bad partisanship. The way to overcome that is not to seek a middle ground with those advancing a backward agenda. It's to defeat bad partisanship with better partisanship.

Division creates accountability

A common critique of the current political environment is that Congress has grown increasingly polarized, with Republicans and Democrats nearly always voting as a block, resulting in gridlock.

It is true that, over the last 40 years, partisanship has increased in both chambers, although it has been more pronounced among Republicans in the last 20 years.

Partisanship has slowed down the workings of Congress but has not brought it to a halt. Obama was able to pass Obamacare and a stimulus package. Trump got his tax cut. None of those policies were passed with bipartisan support.

America is becoming more like a parliamentary system, where the party in power has near complete control of the legislative agenda. That comes with an often overlooked feature: accountability.

Voters only vote for one representative. But partisan polarization allows them to hold an entire legislative body accountable since each candidate is a rough proxy for an overall agenda. A fan of Trump's tax cuts? Vote for the Republicans, who nearly unanimously supported the legislation. Want an approach that does more to boost the incomes of working Americans? Vote for the Democrats, who unanimously opposed the tax cuts.

We saw the converse in 2004, where John Kerry ran on a platform of opposition to the Iraq War. The argument was not as compelling as it could have been, however, since the war was authorized with huge bipartisan majorities, including Kerry.

Partisanship gets voters to the polls

The conventional wisdom is that partisan politics turns off voters and sours them on the political process. This is false.

Op-ed writers seek technocratic compromises, but voters crave clear differences. Partisan politics brings voters to the polls, and that's a good thing. Pietro S. Nivola of the Brookings Institution explains:

Marc J. Hetherington of Vanderbilt University demonstrates… voter participation has surged as the partisan divide has grown sharper.

The electorate is not turned off by the chasm, and contestation, between the parties. On the contrary, Hetherington finds, the polarized political parties have animated voters of all stripes—liberals, conservatives, and moderates. Growing civic engagement and voter turnouts are hallmarks of a vibrant democracy, not of a “broken” one.

This is also why turnout in party primaries, where the differences between candidates are smaller, is always lower.

There has been a dramatic rise in political independents in recent years. But that growth is mostly comprised of political partisans who do not want to affiliate formally with a party. True independents, who have no strong ideological leanings, tend to be uninformed and politically inactive.

Liberals, the reluctant partisans

The main difference between liberal partisans and conservative partisans is that the liberals feel bad about it. Muirhead details the problem:

[T]he problem with liberals is that they are reluctant to admit they are in a partisan contest -- and to fight effectively, they need to become less embarrassed by their own partisanship. Liberals tend to believe… they are simply being reasonable and rational. As a result, they expect others will come to the same views as theirs through nothing more than reasoning about evidence… they see their goals supported by common sense and their policy preferences supported by social science.

This is what many liberals get wrong. They will not convince their opponents through reason and social science. They must engage in political combat.

Thanks for reading! Send me feedback at judd@popular.info.

This is the free weekly edition of Popular Information. Paid subscribers receive four newsletters every week. Subscriptions are $6 a month or $50 for an entire year.

The weakness in our system isn't partisanship, it's the winner-take-all nature of our 17th C. election system (first-past-the-post) and the use of single member districts, where a candidate with a plurality of votes gets 100% of the power to "represent" that district. We get radical swings across the policy spectrum for a country of 330 millions thanks to a tiny handful of votes in key districts. The key to getting the benefits of partisanship without so much of the negative cost is getting rid of the single-member-district law for the US House that was a well-intended but misguided response to the anti-civil-rights shifts in the southern states after the Voting Rights Act. States wanted to go to "At large" elections for congress to ensure that minorities would be locked out ... a better solution would have been to move to proportional representation systems that allow the majority to elect a majority of seats, but also ensure that minorities can win seats in rough proportion to their numbers. In all but the smallest states, you can have multimember districts, and a lot more states would be "purple," with everyone in the state feeling that they actually have someone in the House representing them -- which is most assuredly not the case today, where our gerrymandered districts produce a geriatric Congress that has better protection from competition than the British House of Lords.