Voices of San Quentin: The inside story of how a prison became the nation's biggest COVID cluster

An aerial view of San Quentin State Prison. (Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

For this issue, Popular Information collaborated with Voices of San Quentin (VOS), a group that amplifies voices inside and beyond the walls of San Quentin State Prison. We’ve included soundbites from VOS’s interviews with members of the San Quentin community throughout the piece. Check out VOS on Twitter or Instagram.

San Quentin State Prison hit a grim milestone this month: it recorded its 25th prisoner death from COVID-19.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, prisons and correctional facilities have been some of the largest virus hot spots. Today, the 10 biggest clusters of COVID-19 infections in the United States are in prisons and jails, according to data from The New York Times. A study from John Hopkins University and UCLA found U.S. prisoners are 5.5 times more likely to test positive for COVID-19 and three times more likely to die than the general population.

Located just north of San Francisco, San Quentin is currently the largest cluster of cases in the nation, with 2,608 confirmed cases according to the New York Times. In less than three months, the virus infected almost 70% of San Quentin’s prison population.

Experts believe this public health disaster was completely preventable. For months, San Quentin managed to avoid an outbreak. But when the virus arrived at the deteriorating facility, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation’s (CDCR) inadequate response made the situation drastically worse.

In recent weeks, the number of new cases at San Quentin have started to slow down. Though this is encouraging, it does not mean that the prison has figured out how to control the spread of the virus. Most inmates at San Quentin have already contracted COVID-19. The factors that led to this disaster in the first place – a combination of negligent leadership and deteriorating prison conditions – persist.

In the past 14 days, the CDCR reports San Quentin added 13 new cases, bringing the number of active cases in custody to 76. But these numbers are likely an underestimation. Voices of San Quentin (VOS) reports that some prisoners are refusing testing out of fear of being forced to move cells or placed into solitary confinement.

Months later, the virus is both a haunting memory and a continuing threat.

From zero to 2,608

Until the beginning of June, there had been virtually no coronavirus cases at San Quentin – a remarkable feat considering that the virus began rampaging through prisons and jails as early as March.

Then, on May 30, the CDCR transferred 121 prisoners from the California Institution for Men in Chino to San Quentin. At the time, Chino had the largest recorded outbreak of any California prison. To curb the virus’s spread, prison officials decided to transfer medically vulnerable prisoners to COVID-free facilities.

When prisoners at San Quentin became aware of this plan, they were worried. Christopher Scull, who was incarcerated at San Quentin at the time, told VOS that when he asked the warden, “Isn’t that where the COVID-19 outbreak is?” the warden responded, “Yes, but I can’t stop these buses from arriving.”

San Quentin’s residents had their worst fears confirmed. Aside from temperature checks, none of the Chino prison transfers, including four who had shown virus symptoms before getting off the bus, were tested in the weeks prior to or upon arriving at San Quentin.

The transfers were not quarantined, according to The San Francisco Chronicle. Instead, the newly arrived inmates were placed in poorly ventilated cells before being distributed throughout the prison. Less than a week later, San Quentin began reporting its first cases: 15 of the prisoners who transferred from Chino were infected with the coronavirus, according to the Chronicle.

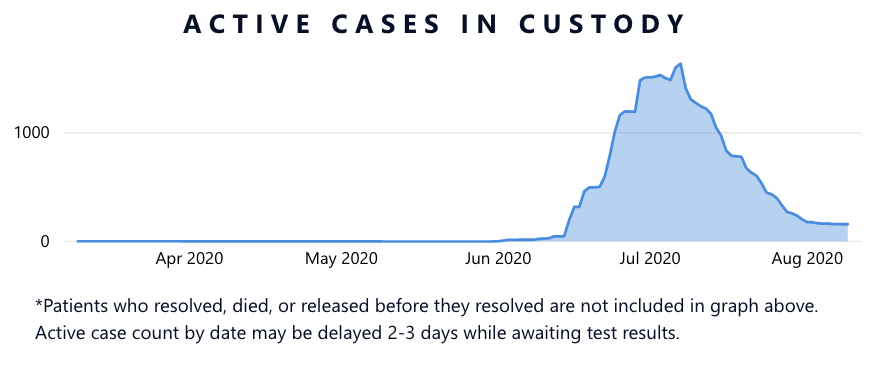

Population COVID-19 Tracker from California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

Within two weeks, the number of daily active cases at San Quentin ballooned from 15 to 498. By the end of June, daily active cases had surged to 1,509, and peaked at 1,635 on July 7. What was once a COVID-free facility, became a disaster zone.

The crackdown

When the virus began to circulate, the prison cancelled all activities. Hot meals were halted, a 23-hour lockdown was imposed, and residents were forced to choose between taking a shower or making a phone call every three to five days. But these efforts weren’t enough to stop the spread of the virus at the overcrowded and poorly maintained facility.

Prisons are not designed to withstand public health threats, especially when spacing people out is a requisite. In California, most prisons are dangerously overcrowded and San Quentin is no exception. Before the arrival of COVID-19, San Quentin was operating at 118% overcapacity. With most men sharing cells (many as small as 4-by-9 feet), shower stalls, and phones, it is practically impossible to practice social distancing.

San Quentin is also California’s oldest prison and suffers from years of neglect. “Given the unique architecture and age of San Quentin (built in the mid 1800s and early 1900s), there is exceedingly poor ventilation, extraordinarily close living quarters, and inadequate sanitation,” wrote UC Berkeley and UCSF health experts after visiting the prison on June 13.

Strapped for space, officials moved those who tested positive or were exposed to someone who tested positive to solitary confinement as cases began ticking up. “It’s like being punished because they have the virus,” said Al Fredericks, who was formerly incarcerated at San Quentin, to VOS. Eventually, by July, the prison set up tents in the yard to house infected residents. In some cases, prison officials locked in infected residents with non-infected cellmates, residents told VOS.

“If you had a cellie and he’s positive and you’re not, they’re gonna lock both of you in there,” said Chanthon Bun, who was released early from San Quentin in July, to VOS.

Currently, residents can only leave their cells every three days for a specified time period to shower, make phone calls, and, if they still have enough time, exercise in the yard. Experts warn that these measures are not sustainable. Cells at San Quentin are not meant to be occupied for days on end; under normal circumstances, residents would be spending the majority of their time outside of their cells.

“This breakout is so severe, they've got us on full lockdown. I'm getting out my cell once maybe every three days for a shower and a phone call. The rest of the time I'm locked in. I'm talking about completely locked in with another man,” said San Quentin resident Rahsaan Thomas on August 5. “So it's like living in a bathroom with another person. And the thing about San Quentin, it has the tiniest cells of any prison.”

Moreover, due to contraband policies, access to antiseptic products like hand sanitizer and cleaning supplies is heavily restricted. While the prison has taken steps to install sanitizer dispensers in some units, it is still unclear if these products are widely accessible. When Popular Information inquired if the prison was distributing hand sanitizer and disinfectants, VOS shared that one San Quentin resident replied “What hand sanitizer? What disinfectant?” He shared that over the course of five months, he had only seen these products twice. Unable to practice basic sanitation, prisoners are left practically defenseless against the virus.

A few weeks ago, the CDCR reported that tents set up to house infected patients were “decommissioned due to significant reduction in cases.” This sharp decline is promising. But anecdotes from the inside reveal that little has changed.

“I feel like they’re trying to let everybody catch it so they could say, OK, everybody got it here so we can just resume,” said Brian Asey, a prisoner at San Quentin, to VOS.

The new clusters

While cases at San Quentin have declined, CDCR data shows that there have been 1,159 new confirmed cases in California prisons in the last two weeks. Five prisons reported more than 100 new cases. One prison, CA Correctional Institution, reported 211 new cases over the past 14 days. Other facilities nationwide are also suffering a surge in cases. According to a tracker maintained by The Marshall Project, there were at least 3,808 new cases in Florida and 1,427 in Texas reported among prisoners the week of August 11.

Moreover, these outbreaks don’t just endanger incarcerated populations; they impact correctional officers, medical staff, kitchen cooks, chaplains, and hundreds of other workers who enter in and out of prisons each day. Earlier this month, the first San Quentin employee died of COVID-19. CDCR data reveals that a total of 272 San Quentin staff have tested positive for the virus. When an outbreak occurs at a prison, it can spread and quickly compromise a community’s public health capacity.

Mass incarceration is a public health issue

When public health experts toured the San Quentin facilities in June, they recommended “that the prison population at San Quentin be reduced to 50% of current capacity via decarceration” and added that “even further reduction would be more beneficial.”

During a press conference, California State Senator Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco) explained that decarceration efforts were a long time coming: “This is a humanitarian disaster that is compounding another humanitarian disaster called mass incarceration. And we need to be very, very clear that what's happening in San Quentin and what may happen if we don't really change things at other prisons. It's not just because of COVID-19. It's because the state of California for 40 years now has been completely addicted to incarcerating more and more people for longer and longer sentences. And it doesn't have to be that way.”

Since March, the CDCR has reduced California’s prison population by more than 10,400. Governor Gavin Newsom (D) also announced that 8,000 prisoners across California will be released early by the end of this month. But some believe this step is not nearly aggressive enough. Philip Melendez, a decarceration advocate, tells Bloomberg Citylab that releasing 8,000 people would shrink the state’s prison population by only 7%.

Some people like to think of the prison population as cordoned off from the rest of society, and to an extent that's true, but prisoners getting released and individuals who work there being active members of their communities, it's not as remote as it may seem re COVID-19.

Mass incarceration, especially now, is indeed a public health issue. There are human beings in these detention centers, jails, and prisons, and no matter what they have done to be locked up (assuming it even warrants being held and to such an extent), they don't deserve to have their lives put in jeopardy from this disease.

This is an excellent piece, y'all. Great job, Tesnim! I loved hearing the from those currently or recently incarcerated; it added so much to the story to be able to hear their voices. Thank you for shining a light on one of our most vulnerable, least-considered populations.