Walmart claims low prices require long prison terms

Walmart CEO Doug McMillon announced during an interview on CNBC last week that the retailer may have to raise prices or close stores due to insufficiently aggressive prosecution of retail theft. McMillon claimed that, as a result of lenient sentences, theft at Walmart is “higher than what it has historically been.” During the interview, McMillon does not disclose how much merchandise Walmart is losing to shoplifting or how that compares to previous years.

Walmart, the nation’s largest retailer, racked up $559.2 billion in revenue last year. So far this year, the company has made $15 billion in profits. Last quarter alone, Walmart recorded $152.8 billion in sales, nearly a 9% increase from the previous year. The purported spike in shoplifting at Walmart did not stop the company from announcing a new $20 billion share buyback plan last month. And McMillon is being paid as if the company is thriving. In 2021, he took home $22.574 million in total compensation — 1,078 times more than the median Walmart employee.

Publicly available data also contradicts McMillon’s claims. As Popular Information previously reported, the number of shoplifting offenses dropped 46 percent between 2019 and 2021, according to the FBI’s crime data explorer.

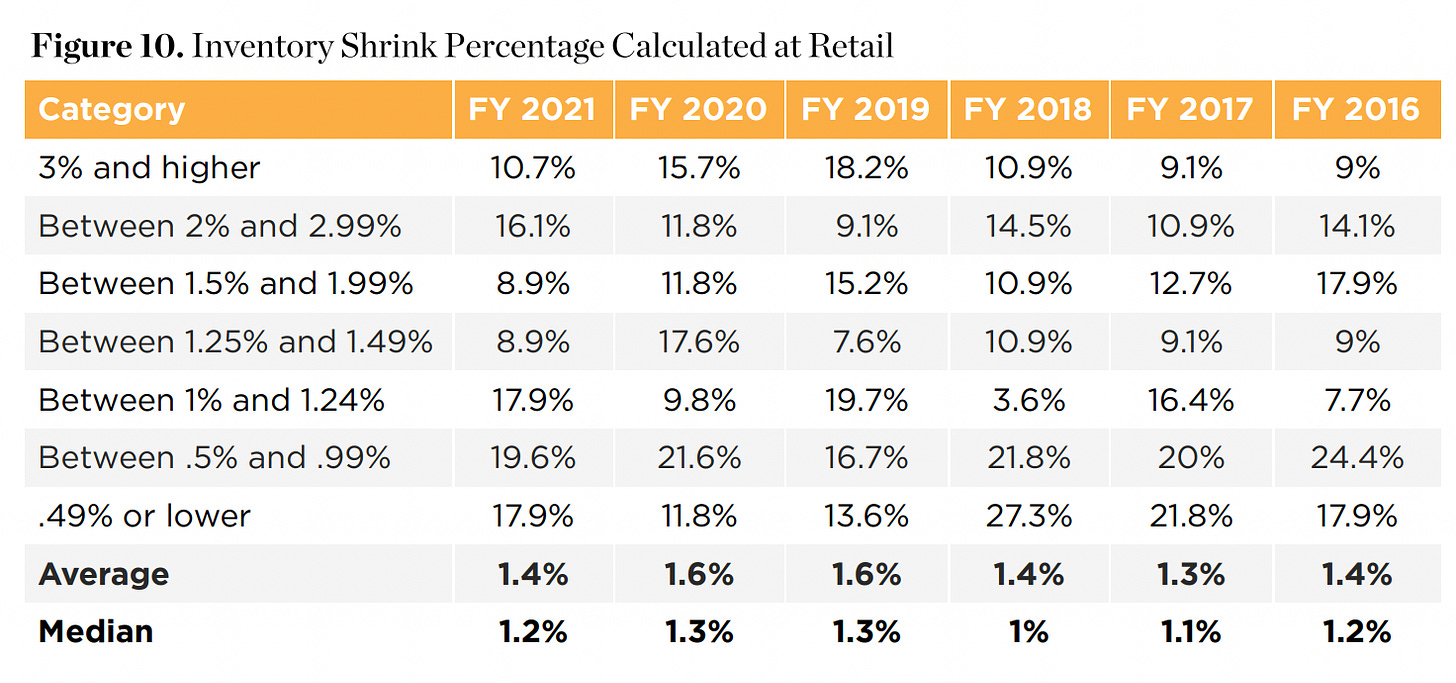

Of course, not all shoplifting incidents result in charges. But the National Retail Federation, a trade association that represents Walmart and other major retailers, found that "shrink" — an industry term for inventory losses from theft, damage, or administrative errors — declined between 2019 and 2021. In 2021, the average shrink rate was 1.4% of total retail sales. That means for every $100 in sales, an average of $1.40 in inventory was lost. Retail theft alone amounted to 0.5% of total retail sales, or $0.52 for every $100.

The average retail shrink in 2021 is the same as it was in 2015. The only difference is that shoplifting and external theft made up a slightly larger portion of the "shrink" in 2015 than it did in 2021.

Walmart isn’t the only company stoking fears of a shoplifting surge. Last year, Walgreens announced that it was closing five stores in the Bay Area due to the “scale of thefts.” Popular Information found that this claim, however, was not reflected in citywide crime data, which showed that in 2020 shoplifting had reached its lowest level since they began collecting data 45 years ago. Walgreens also said in 2019 that it planned to shutter 200 stores as a “cost-saving measure,” reported the San Francisco Chronicle. “[T]he timing of Walgreens’ decision led observers to wonder whether a $140 billion company was using an unsubstantiated narrative of unchecked shoplifting to obscure other possible factors in its decision,” wrote the San Francisco Chronicle.

Target CFO Michael Fiddelke told CNBC last month that theft rose “about 50% year over year.” The company told Winsight Grocery Business that it is working with legislators and law enforcement to address the “growing national problem” of retail theft. Similarly, last week, the former CEO of Home Depot, Bob Nardelli, described retail theft as an “epidemic” and said that shoplifting was “spreading faster than COVID.”

Despite the apocalyptic rhetoric, losses from shoplifting pale in comparison to the wages employers steal from employees each year. The Economic Policy Institute estimates that employers steal roughly $15 billion annually from their employees from minimum wage violations alone. This figure, which excludes other common forms of wage theft like overtime violations, “exceeds the value of property crimes committed in the United States each year.”

Since 2000, Walmart has had to pay $1.5 billion in penalties for wage and hour violations, according to the Good Jobs First Violation Tracker.

Will more aggressive prosecution deter theft?

CNBC's Rebecca Quick, one of the hosts of Squawk Box, asked McMillon about "laws that have been changed." Specifically, Quick claims that there are new laws that provide "criminals won't be prosecuted below a certain level." McMillon accepted the premise of Quick's question, arguing the laws need to be "corrected."

But Quick's description of the law is inaccurate. States have not passed statutes legalizing theft. Rather, all states have a felony threshold for shoplifting. In Connecticut, shoplifting more than $200 in goods is a felony. In Texas, the threshold is $2,500. Misdemeanor theft, below the felony threshold, generally results in little to no jail time. Felony theft can result in years in prison.

Since 2000, at least 40 states have raised their felony theft thresholds. Walmart and other retailers have spent millions opposing these changes, arguing that raising the felony threshold will increase shoplifting. The data, however, does not support this claim.

A 2017 study by Pew Trusts found that "in the 30 states that raised their thresholds between 2000 and 2012, downward trends in property crime or larceny rates, which began in the early 1990s, continued without interruption." Further, the study found that "states that increased their thresholds reported roughly the same average decrease in crime as the 20 states that did not change their theft laws." Notably, the "amount of a state’s felony theft threshold—whether it is $500, $1,000, $2,000, or more—is not correlated with its property crime and larceny rates."

In 2010, South Carolina raised the threshold for felony theft from $1,000 to $2,000. Pew Trusts found that "since the law was implemented, the state’s property crime rate …continued to fall, dropping 15 percent in the three years after reform." Despite the higher threshold, "the value of goods reported stolen in the state…did not change, remaining about $200 on average."

Retailers were able to push through a harsh anti-shoplifting law, with no felony threshold, in Arizona. It resulted in a "man who robbed [a] Walmart of goods worth less than $10… facing two felony charges."

Why doesn't increasing the felony threshold increase shoplifting? Most shoplifters are not making a calculation about the potential legal consequences. Many are addicted to drugs and are willing to do anything to feed their addiction. Last month, Walmart proposed paying $3.1 billion to settle lawsuits alleging it "improperly filled prescriptions" for opioids, fueling an addiction epidemic.

Does the CEO or the Wal-Mart corporation have any significant investment in for-profit prisons? I am trying to understand the motivation for pushing this story if it isn't true.

Another criminal organization. Walmart wants to crack down on "shoplifting" that they say is negatively affecting their business. But the evidence goes against their argument. Yet every day our local Walmart is breaking the law with regards to wages paid, hours offered, insurance or lack thereof, price gouging, etc. We need to have a governmental body exercising the proper authority to rein these criminally conspiritorial behemoths in!