Bad Bunny’s dancers, Kalshi, and the insider trading problem

Prediction markets, including Kalshi and Polymarket, are exploding in popularity. Kalshi alone saw over $1 billion in trading volume on Super Bowl Sunday.

Remarkably, more than $100 million was wagered on what song Bad Bunny would play first during his halftime show. That kind of market has raised concerns about insider trading. Not only is Bad Bunny in control of which song is played, but this information is also known in advance by dancers, musicians, crew, and anyone who happened to be around during rehearsals.

This is likely why, just before the big game, Kalshi CEO Tarek Mansour announced a laundry list of efforts to crack down on insider trading. This included partnering with a forensics lab, hiring an intelligence advisor, setting up a “surveillance audit committee,” and investing in “behavior monitoring and pattern recognition tools.”

Mansour said that “insider trading erodes trust” and when “people believe a market is unfair, they stop trading.” Serious violations, Mansour said, would be referred to the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) for criminal prosecution.

One issue, however, is that the CFTC is a relatively small government agency with a budget of less than $400 million and limited experience prosecuting insider trading.

More fundamentally, all of these steps depend on a functional definition of insider trading for prediction markets.

Mansour appeared on CNBC on Tuesday and was pressed on what constituted insider information in a market like Bad Bunny’s first Super Bowl halftime song. Andrew Ross Sorkin asked if Kalshi would consider it insider trading if one of Bad Bunny’s dancers, who knew the first song in advance, bet in the market.

Mansour said that the same rules applied to Kalshi bets as the stock market. He said that anyone who trades on “material non-public information” on Kalshi violates insider trading rules.

The hosts, however, point out that executives of publicly traded companies have a legal obligation not to share financially material non-public information outside of regular public disclosures. Bad Bunny and his employees do not face the same legal constraints and have nothing to do with the market set up by Kalshi.

Mansour offered a pat response: “Either this information can be public, and that’s okay, or it’s information that cannot be public beforehand.”

Mansour appears to be leaning on the CFTC’s more lenient stance toward insider trading. Under CFTC rules, trading on non-public information is permitted, as long as you didn’t obtain the information through fraudulent or illegal means:

The failure to disclose information prior to entering into a transaction, either in an anonymous market setting or in bilateral negotiations, will not, by itself, constitute a violation. However, depending on all of the facts and circumstances, trading on the basis of material nonpublic information in breach of a pre-existing duty (established by another law or rule, agreement, understanding, or some other source), or by trading on the basis of material nonpublic information that was obtained through fraud or deception, may violate final Rule 180.1.

“This has been an age-old question for all types of financial markets, right?” Mansour asked rhetorically. “Should the farmers be able to trade on grain futures, you know, because they have more information about the crops?” Farmers are allowed to trade on grain futures.

Becky Quick, the other CNBC host, noted that if that is the standard, dancers who knew the song in advance would be free to participate in the Kalshi market:

It’s not material information that can’t be shared. You’re making it that by putting it on this betting platform, but they have no obligation to say we’re not going to tell anybody our opening lineup because there might be money made on this other place that’s now betting on this… the responsibility is not on them.

Mansour conceded the point. “If that’s the position that people are taking… It’s basically, you know, it’s okay to actually talk about which song is gonna be played… then that it’s okay and it’s totally fair game, and I agree with you in that case,” he said.

“That just doesn’t seem like a fair market trade,” Quick replied. “[T]here’s an advantage to people who have this information [and] there’s no way you could go after them because it’s… this is not material information.” The discussion concluded with Mansour suggesting that Bad Bunny revealing the song in advance to people who place bets on Kalshi was “fair game” and part of “the risk in the market.”

In response to Popular Information’s request for comment, Kalshi provided the following statement:

People who participate in large commercial events, activities, etc often sign contracts or agreements not to disclose info, maintain confidentiality, etc. Where users have a legal duty not to disclose info and then they do disclose it, it can be insider trading. Of course, cases depend on specific facts and evidence.

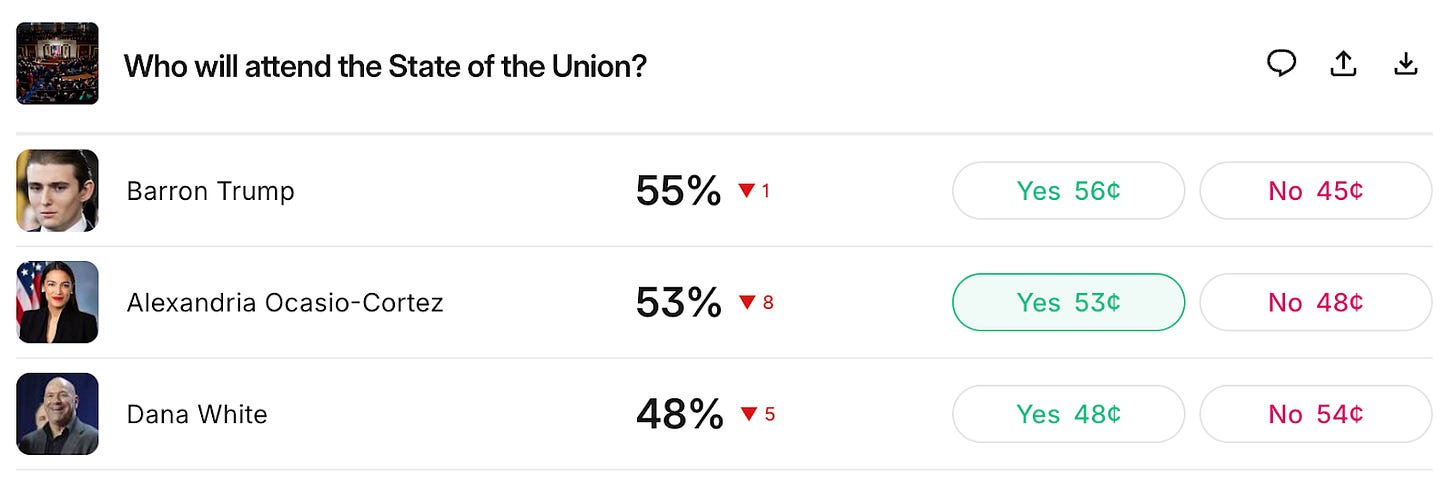

Numerous markets offered on Kalshi carry similar risks. For example, there are individual markets on whether dozens of people will attend President Trump’s State of the Union address on February 24.

At some point before the speech, Barron Trump will know whether he’ll attend. There is nothing to stop him from telling his buddies at New York University. Barron Trump is not obligated to keep his plans secret because Kalshi has set up a market.

As someone who doesn’t gamble, perhaps I’m missing how this easily rigged, permissive odds-making model isn’t considered an obvious, silly scam by most would-be users. The temptation to trade on insider info is enormous (and not against the rules…!?)

So, Mansour's response to the idea that Bad Bunny's dancers betting based on insider information doesn't sound like a fair trade is to...insist that, no, it *is* fair? Pardon me if I'm not convinced. Kalshi sounds like another financial market that will go dangerously un- or under-regulated. Concerning, to say the least.