The casino-fication of news

New partnerships between the prediction market Kalshi and cable TV networks will transform every news event into a betting opportunity.

Two major news networks, CNN and CNBC, recently announced partnerships with Kalshi, an online predictions market. Kalshi allows the public to place bets on a dizzying variety of news events. There are currently Kalshi markets for the winner of the 2028 presidential election, next month’s unemployment rate, next week’s top TV show on Netflix, whether the announcers will say “Cheesehead” during Sunday’s Green Bay Packers football game, and thousands of other future events.

The CNN deal, which starts immediately, involves the “integration of Kalshi data across CNN programming“ and “a new Kalshi-powered real-time news ticker that will run during segments that feature Kalshi data.” The CNBC deal, which begins in 2026, will “incorporate real-time prediction data into CNBC’s editorial coverage across its TV, digital, and subscription channels.” Kalshi will also create “a CNBC page on its site, featuring CNBC-selected markets.”

The economic terms of the arrangement between Kalshi and the two networks were not disclosed.

Unlike other prediction markets, Kalshi has sought regulatory approval from the U.S. Commodities Futures Trading Commission (CFTC). After winning a lawsuit against the CFTC that allowed it to take bets on the 2024 presidential election, the platform has exploded in popularity. Trading volume is expected to exceed $50 billion in 2025, up from $300 million in 2024.

The new partnerships with CNN and CNBC will not only draw more users to Kalshi but fundamentally change the nature of news. It is no longer just a mechanism to learn about and understand world events. The news is now an opportunity to speculate on future events for financial gain.

“Kalshi is replacing debate, subjectivity, and talk with markets, accuracy, and truth,” Kalshi CEO Tarek Mansour said in a December 2 press release. “We have created a new way of consuming and engaging with information.” CNN and CNBC, two of the most prominent news outlets in the world, are endorsing and legitimizing this model of journalism.

These deals take a style of reporting popularized by election polls — horserace-style coverage that emphasizes who is ahead or behind — and expands it to virtually every topic. The gamified coverage is paired with the promotion of a company, Kalshi, that allows the public to place wagers on the outcome of these events.

How the wealthy can manipulate and distort prediction markets — and the news

Treating Kalshi’s betting markets as “news” is based on the Efficient Market Hypothesis, which contends that a liquid market reflects the best information available. According to this theory, while reporters are biased and polling is flawed, betting markets like Kalshi reveal the best approximation of the “truth.”

There are a few problems with this theory. First, while Kalshi is growing rapidly, it is still very small compared to the stock market. $50 billion in annual volume is about $135 million in volume per day. Most of Kalshi’s trades are related to sports events — over 75% according to one recent study — so the markets for current events are even smaller. In contrast, according to the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA), there is about $610 billion in daily trading volume for U.S. equities.

Since volumes are exponentially lower, this leaves Kalshi markets much more open to manipulation than the stock market. Now that movement in Kalshi markets will be treated as news on CNN and CNBC, the incentives for market manipulation are even greater.

If a political Candidate A was facing a corruption scandal, for example, a wealthy benefactor could place a large bet predicting that Candidate A would win. It takes no more than a few million dollars, and usually much less, to move a political prediction market substantially. The change in the market will now be treated by CNN and CNBC as “news” and, potentially, evidence that the corruption scandal is not damaging Candidate A’s prospects. The manufactured positive coverage of Candidate A could also crowd out coverage of the corruption scandal itself.

Alternatively, someone could seed a false rumor on social media that Candidate X was dropping out of the race, then place a large bet on the opponent, Candidate Y. When the price for Candidate X to win moves significantly lower, CNN would report that as news, fueling the rumor mill on social media and driving the price of Candidate Y up further. The originator of the false rumor could then sell their position in Candidate Y for a profit before it became clear that the rumor about Candidate X dropping out was false.

Ultimately, the Efficient Market Hypothesis contends that where people spend their money reflects the truth. But in an era of extreme wealth inequality, treating movements in relatively small markets like Kalshi as news is not justifiable. The movements in markets may reflect conventional wisdom, but they could just as easily reflect what wealthy people want others to believe.

The insider trading problem

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has a sophisticated system to prevent, identify, and prosecute insider trading. Some insiders are required to sell their shares only at pre-announced intervals to prevent profiting from non-public information. The SEC benefits from the fact that, at publicly traded companies, the people with access to inside information are relatively limited and well-defined.

There are also sophisticated algorithms that identify suspicious trading from people who may be getting tipped off by insiders.

In addition to automated systems, the SEC offers large whistleblower rewards to individuals who tip the agency off to insider trading. Once insider trading is identified, the agency aggressively prosecutes offenders, seeking civil and criminal penalties, including jail time.

In contrast, the CFTC, which regulates Kalshi, does not prohibit the use of inside information. Most markets regulated by the CFTC are used to mitigate risk. This often involves companies using insider information. A major airline planning an expansion, for example, could purchase jet fuel futures, anticipating that its expansion would drive jet fuel prices higher. By buying jet fuel futures, the company locks in fuel at the current price. This is not only legal but is seen as prudent financial management.

The CFTC does have rules against using inside information to manipulate a market. But purposeful manipulation is very difficult to prove.

Further, since the CFTC does not prohibit insider trading, its resources for identifying and prosecuting bad actors are far more limited than those of the SEC. It has no mechanism or experience monitoring the large and diffuse networks of people who could be using inside information to manipulate any of the thousands of markets on Kalshi.

Kalshi’s rules prohibit trading on “material non-public information” or if you “have the ability to influence the outcome,” but it is unclear what resources Kalshi deploys to enforce these rules.

Trivializing the news

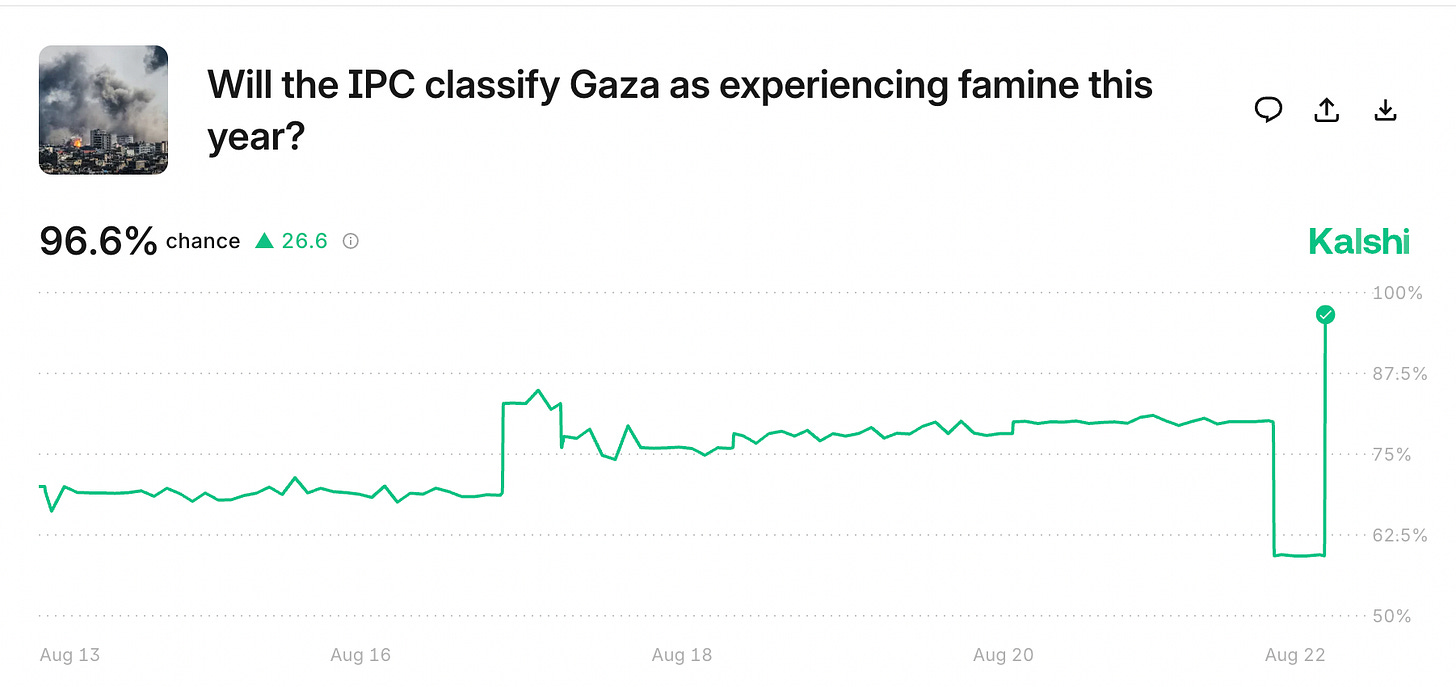

The integration of Kalshi into news coverage can trivialize even the most sobering events, framing tragedies as money-making opportunities. For example, Kalshi offered a market allowing people to bet on whether there would be a famine declared in Gaza this year:

Since the IPC declared there was a famine in Gaza in August, there are people who used Kalshi to profit from the starvation of other people.

A bad bet

The CNN and CNBC deals will promote Kalshi to a new audience that may be unaware that news prediction markets exist. These markets are similar to gambling in that they offer variable rewards, making them addictive. Like gambling, most people also lose money.

Stocks, over the long term, tend to go up in value. So purchasing equities, which is also a kind of “bet,” has a positive expected value.

Prediction markets, however, are zero-sum. For every prediction, there is one outcome, and someone wins, and the person on the other side of the bet loses. Because Kalshi collects a fee, its users are guaranteed, on aggregate, to lose money. One academic study found that, even before fees, Kalshi users lost an average of 20%. This suggests that sophisticated bettors have an advantage over typical users.

This is bad. Gambling brings out the worst in us. Like the human desire to dictate unrelated individual outcomes like the roll of a die as part of some mythological Law of Probabilities. How many times have I heard that from friends who gamble? Efficient Market Hypothesis as some bringer of truth by replacing discussion and subjectivity? Very bad. Betting on famine in Gaza? Very bad and disgusting.

So long CNN & CNBC. I remember you when.