Thousands of Adnan Syeds are still behind bars

On Tuesday, Adnan Syed was set free. He had been detained since 1999, when he was arrested as a 17-year-old in connection with the killing of Hae Min Lee, his ex-girlfriend. Syed was convicted of first-degree murder, robbery, kidnapping, and false imprisonment on February 25, 2000. His sentence was life in prison plus 30 years.

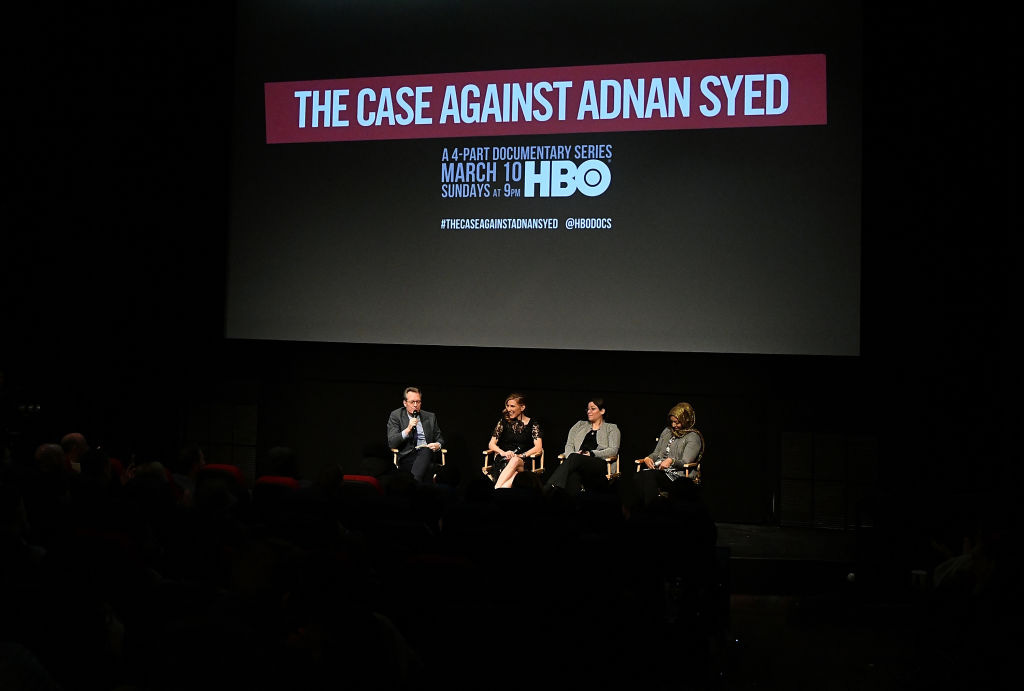

Syed always maintained his innocence. The weaknesses in the case against him were featured in a hit podcast, an HBO documentary, and a best-selling book. And, after his conviction, he enjoyed the assistance of a phalanx of talented pro bono lawyers. It still took almost 23 years for Syed to win his freedom. He is now 41.

In 2016, Syed's conviction was vacated by a Baltimore judge, and he was granted a new trial. The basis of that decision was that Syed received ineffective assistance of counsel. Among other things, Syed's original attorney, Maria Cristina Gutierrez, declined to cross-examine a key expert witness for the state and failed to call a potential alibi witness on Syed's behalf. Gutierrez, who died in 2004, was disbarred the year after Syed's trial "after a state commission uncovered financial improprieties involving her clients."

But in 2019, Maryland's highest court, the Court of Appeals, reversed the trial court's decision and reinstated Syed's conviction. The court didn't dispute that Gutierrez had likely made mistakes but found, "given the totality of the evidence…there was not a significant or substantial possibility that the jury would have reached a different verdict."

Despite the talented attorneys working on his post-conviction appeals, Syed won his freedom only after a Baltimore prosecutor, Assistant Baltimore State’s Attorney Becky Feldman, voluntarily agreed to take another look at Syed's case alongside one of his attorneys, Erica Suter. Feldman conducted a one-year investigation and "discovered evidence of two alternative suspects." One of those suspects had threatened to kill Lee in the presence of a witness.

Feldman also "found instances in which authorities withheld information from his defense."

Feldman and State's Attorney for Baltimore Marilyn J. Mosby filed a motion to vacate Syed's conviction on September 22. That motion was granted by the court, and Syed was placed in home confinement pending a final resolution. On Tuesday, Feldman informed the court that the state did not intend to retry Syed, and he was released.

While Syed ultimately won his freedom, his case revealed a fundamental weakness in the American criminal justice system. Despite intense interest in his case and access to top legal talent, it still took decades for Syed to be released. Thousands of other wrongfully convicted individuals lack Syed's resources and remain behind bars.

The scope of wrongful convictions in the United States

According to peer-reviewed, academic research, about "6% of criminal convictions leading to imprisonment" in state courts are "wrongful convictions." Those who are wrongfully convicted include factually innocent people and those who had their procedural rights violated.

The most common source of wrongful convictions are "witnesses who lied in court or made false accusations." Other common issues leading to wrongful convictions include "mistaken eyewitness identifications, false or misleading forensic science, and jailhouse informants." In other cases, "innocent people confess to crimes they did not commit." Of the first 250 people exonerated for rape and murder by post-conviction DNA analysis, 40 falsely confessed. This is sometimes due to specific interrogation tactics that can elicit false confessions.

Since 1989, 3,264 wrongfully convicted individuals have been exonerated. Those individuals, collectively, have served 28,150 years behind bars. More than half of exonerated individuals are Black. The data shows that "innocent Black people are 19 times more likely to be convicted of drug crimes than innocent whites…despite the fact that white and Black Americans use illegal drugs at similar rates."

The pace of exonerations has accelerated somewhat in recent years. The National Database of Exonerations includes 24 exonerations from 1989 but 172 from 2021.

But, if the academic research is reliable, these exonerations are just the tip of the iceberg. There are currently over 1 million people in state prisons. If 6% of those were wrongfully convicted, that means there are more than 60,000 innocent people in state prisons alone.

A rigged game

The 6th Amendment establishes that people accused of crimes have a right to the assistance of counsel. But it's up to each state to decide what resources to devote to public defenders. Many states dramatically underfund this effort. In 2017, 60 public defenders in New Orleans handled about 20,000 cases annually. Many public defenders are excellent lawyers, but simply lack time to do their job well. Often, defendants are fortunate to get a few minutes of their lawyer's attention.

Once a conviction is affirmed on direct appeal, "people who are wrongly convicted and imprisoned have no right to counsel." Syed had access to excellent post-conviction counsel. But most convicted prisoners don't have lawyers willing to represent them for free and lack the resources to hire them.

Meanwhile, misconduct that can lead to a wrongful conviction almost always goes unpunished. Under current law, prosecutors "can’t be held liable for falsifying evidence, coercing witnesses, presenting false testimony, withholding evidence, or introducing illegally-seized evidence at trial."

Enter the Supreme Court

The situation is already bleak for the wrongfully convicted in the United States. This week, the Supreme Court made the situation even worse. By a 6-3 vote, the Supreme Court declined to intervene in a case where a Black man, Andre Thomas, was sentenced to death by an all-white jury. Thomas was convicted of murdering his estranged wife, who was white, their son, and his wife's daughter from a previous marriage. He confessed to the crime, but "pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity." (Thomas stabbed himself while committing the offense and has removed both of his eyes while incarcerated.) Prosecutors acknowledged he was psychotic when he killed his family but argued "his psychosis was voluntarily induced just before the killings through ingestion of… cough medicine." The jury sentenced him to death.

Prosecutors in the case "questioned prospective jurors about their attitudes toward interracial marriage and procreation." Three individuals said they opposed interracial marriage and procreation but were seated in the jury. "I don’t believe God intended for this," one juror said. Another juror said that they think interracial marriage was "harmful for the children involved because they do not have a specific race to belong to."

Thomas' defense attorney didn't object to any of these three jurors, and in two cases, didn't even bother to question them about their opposition to interracial marriage. On appeal, Thomas' new attorneys argued that the failure to object or even question the racially-biased jurors constituted ineffective assistance of counsel. Justices Sotomayor, Kagan, and Jackson agreed. "The errors in this case render Thomas’ death sentence not only unreliable, but unconstitutional," Sotomayor wrote. "II would not permit the State to execute Andre Thomas in light of the ineffective assistance that he received, and would summarily reverse the Fifth Circuit."

But the six Justice conservative majority on the Supreme Court does not think the failure to object to the racially-biased jurors was unreasonable and is allowing the execution to go forward.

It just goes on and on and on. And yes, we can vote and work toward a safer, fairer world. But in the meantime, the same groups of people get run over and brutalized over and over and over. Thank you for giving us important information, Judd. As Rachel Maddow apparently wants us to “gets from her Ultra podcast, it takes us public members to persuade and keep chipping away at the terribly destructive beliefs of the people of so many who continue the harm, like the members of our Supreme Court.

Excellent report. The Supremes have much to answer for, as does the entire judicial system.