Google's holiday gift to Devin Nunes

In November, Congressman Devin Nunes (R-CA) was in the spotlight — the top Republican on the House Intelligence Committee, which was leading the impeachment inquiry into President Trump. He used his star turn to push "fantastical conspiracy theories" about Democrats. Nunes falsely accused Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam Schiff (D-CA) of trying to obtain nude photos of Trump. He promoted the discredited notion, advanced by Trump but rejected by the intelligence community, that Ukraine took significant steps to meddle in the 2016 election. The debunked contention is part of a broader Russian propaganda effort to absolve itself from hacking the DNC servers by pinning the blame on Ukraine.

Nunes was warned during the hearings by Fiona Hill, a former member of the National Security Council, that he was legitimizing a Russian disinformation campaign. "I refuse to be part of an effort to legitimize an alternate narrative that the Ukrainian government is a U.S. adversary, and that Ukraine — not Russia — attacked us in 2016," Hill said. "In the course of this investigation, I would ask that you please not promote politically driven falsehoods that so clearly advance Russian interests." Nunes was undeterred.

Nunes' antics during the impeachment hearings capped a year when he filed six defamation lawsuits, seeking hundreds of millions in damages from Twitter, a GOP political operative, media companies, a retired farmer, and a fictional cow. The suits were all filed by an attorney, Steven Biss, whose law license was suspended twice by the state of Virginia.

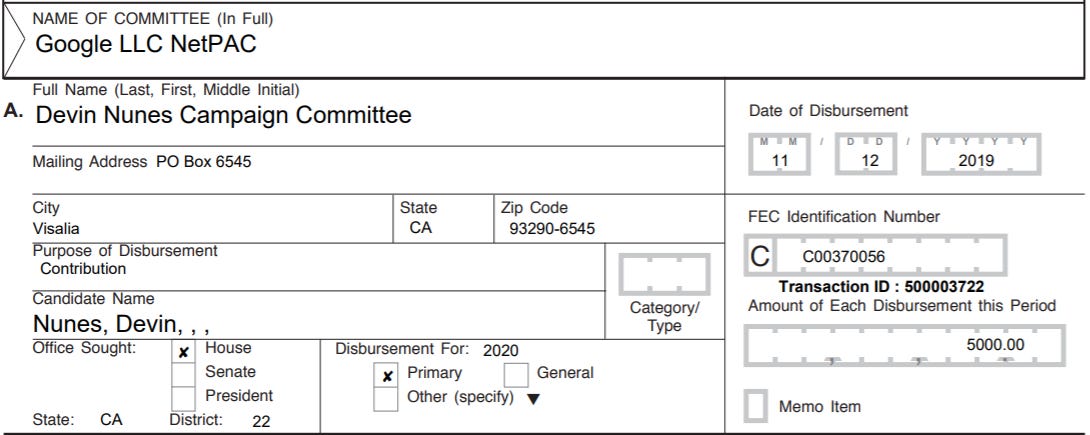

In response, Google quietly rewarded Nunes' behavior with a check for $5000 to help him get reelected. The donation was revealed in a little-noticed FEC report that was filed on December 20.

Google says its "mission is to make sure that information serves everyone." But it is supporting a Congressman who has emerged as one of the most powerful sources of disinformation in the country.

It is a vivid example of a much broader problem that Popular Information has documented extensively. There is a yawning gap between the publicly stated values of powerful corporations and their political activities. A paper published by Harvard Business School (HBS) this month concludes that corporations have "funded, perpetuated, and profited from political dysfunction."

Who, me?

Corporations have a massive influence on the electoral process. In 2018, corporate spending on federal elections was around $2.8 billion. At the state level, "public companies were the largest source of funding supporting partisan groups in state-level races, such as the Republican Governors Association and its Democratic counterpart."

One chapter of the Harvard paper surveyed HBS alumni and found a shocking level of ignorance about the influence of the corporations they work for on the political system.

When asked whether their own companies’ election spending distorted the democratic process, just 4% said yes, while 30% disagreed (27% strongly disagreed). A remarkable 61% responded to this question with “Not applicable” or “Don’t know.”

The authors said the responses from HBS alumni "suggests either that many business leaders have little knowledge of their companies’ political involvement...or that alumni are unwilling or uncomfortable disclosing their companies’ involvement in elections."

But when asked about corporate involvement in politics generally, most HBS alumni agree that corporate political donations are deleterious and warp democracy.

[A]mong HBS alumni who were asked not about their own company but about business as a whole, 60% responded that companies should not have corporate PACs as a vehicle for employees to contribute to candidates the company supports. And 71% of these same alumni believed that the overall business community’s election spending distorted the democratic process.

In other words, HBS alumni believe that corporate political donations are a big problem — but the company they work for is an exception.

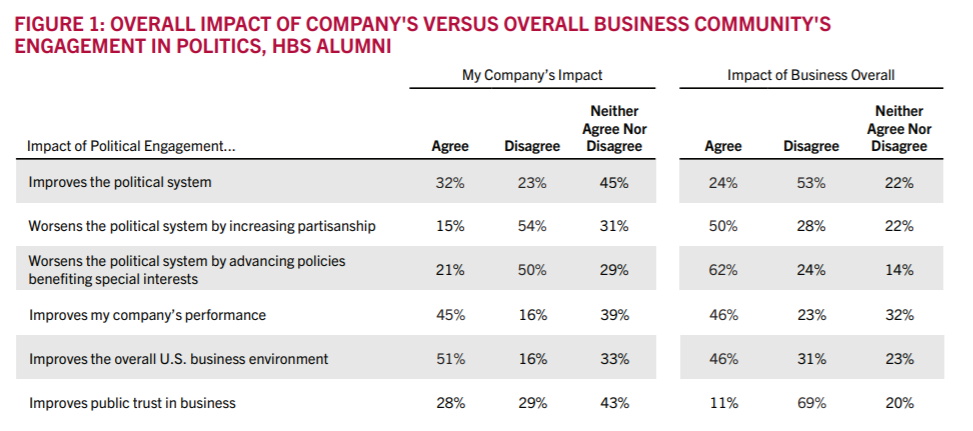

Political donations are part of a corporate "playbook" of political activity that includes lobbying, spending on ballot initiatives, and hiring former government officials. Overall, HBS alumni view their own company's political involvement as largely positive while viewing the activities of all the other companies' political involvement negatively.

Notably, 62% of HBS alumni surveyed say that the business community overall "worsens the political system by advancing policies benefiting special interests," but just 21% are willing to say the same thing about their company.

Short-term gain, long-term pain

While corporate influence campaigns are effectively securing tactical political victories that increase businesses' immediate bottom line, the Harvard study suggests that this strategy is backfiring over the long run.

Based on our research, we believe that much of today’s business involvement in politics may actually be working against business’s longer-term interests. It is not enhancing our nation’s productivity and competitiveness, failing to put business’s weight behind sound public policies to enhance the U.S. business environment, advance shared prosperity among citizens, and improve the communities on which business depends.

This makes sense. Ingratiating yourself with people like Devin Nunes, for example, may help you preserve a valuable tax loophole for another year. After all, he has a vote. It's unlikely, however, that Nunes and his ilk will have any interest in creating a functional social, economic and regulatory environment.

Toward a new meaning of corporate responsibility

Nearly all corporations seek a positive public image, including demonstrating a commitment to creating social good. Up to this point, these efforts have "been in areas like reducing greenhouse gas emissions, improving employee health, and, more recently, paying a living wage and improving training and career development for lower-income workers." Politics has been separate. There is little effort to harmonize corporate political activities with commitments to public responsibility.

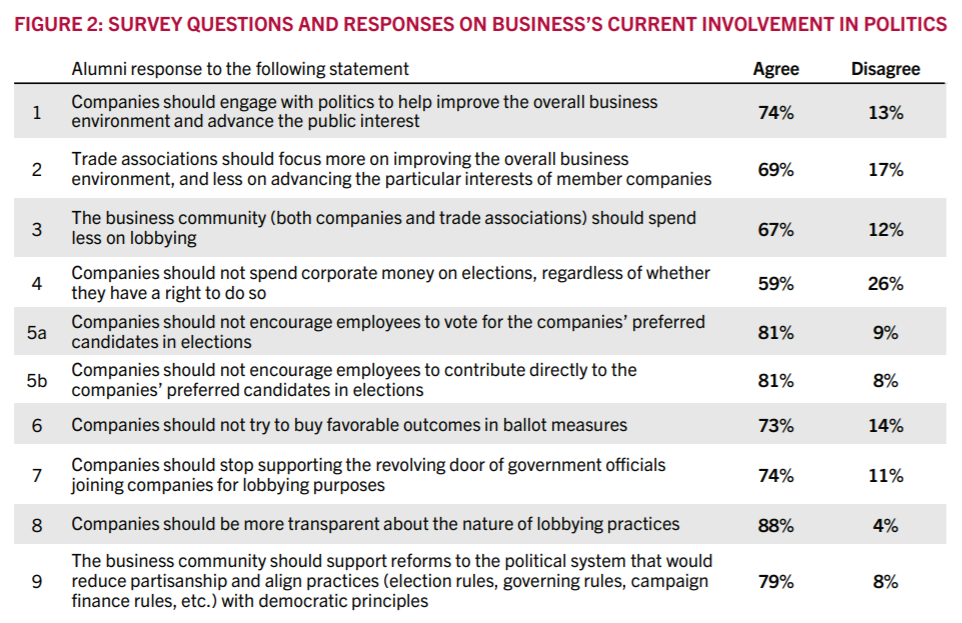

The Harvard study found a surprising willingness among HBS alumni to change the corporate political playbook. A strong majority of HBS alumni believe corporations should end political donations, spend less on lobbying, and stop trying to buy outcomes in ballot initiatives.

This circles back to a dynamic discussed earlier: most corporate employees are unaware (or unwilling to acknowledge) their own company's complicity in the problem. How many Google employees, for example, know their company gave Devin Nunes $5000 last month? Without that knowledge, an abstract willingness to change corporate practices overall will not translate to internal pressure for things to change at a particular company.

Knowledge is only part of the problem. Corporate insiders are often reluctant to speak out, believing that doing so could cost them their jobs.

The author of the Harvard study is proposing a "set of voluntary standards, which we believe every company should adopt when dealing with politics and government." But with so much money at stake, most corporations will not reorient their political activities without a fight. Change, if it does occur, will need to be a product of external and internal pressure.

Thanks for reading!

Devin Nunes is really the worst of the worst. I hope that he is defeated in next November's election.

Nunes is a serious problem. But he & Moscow Mitch are only the outward symptoms of the inner rot that has infected the entire Republican Party. And that rot is quickly spreading into the judicial system like an invasive weed.

Google, in general is seen by consumers as a search company but they do offer many products through which their political contributions might be influenced. A search of Buycott.com https://www.buycott.com/brand/19162/google-upc reveals an extensive list. Vote with your wallet folks. As these corporations have already learned, “Money talks”

Thank you again for the invaluable & informative lesson Judd.