Kroger's “nefarious bargain”

This is a special joint edition of Popular Information and Fingers, a newsletter about drinking in America by journalist Dave Infante. Fingers is a must-read for anyone who cares about the business, culture, and chaos of booze. Sign up HERE.

In January 2022, as COVID case rates soared nationwide, 8,400 workers at Colorado’s King Soopers supermarkets went on strike for better pay, hours, and on-the-job protections from infection and unruly customers.

King Soopers’ 78 Colorado locations are owned by Kroger, one of the largest grocery firms in the country. The company, which generated $4.3 billion in adjusted operating profit in the year leading up to the strike, called the UFCW’s stoppage “reckless and self-serving.” Workers struck for for 10 days, before ratifying a new contract with higher starting wages and better healthcare benefits in early February 2022.

A lawsuit filed earlier this month by Colorado’s attorney general alleges that Kroger had a secret reason to believe it could weather the UFCW strike two years ago without major disruptions to its King Soopers business: a “nefarious bargain” that it struck with rival grocer Albertsons to ensure the latter wouldn’t poach the struck chain’s picketing workers or inconvenienced customers.

“Executives at the very highest levels of both companies knew of this unlawful arrangement and allowed it to go forward,” the complaint claims, citing contemporaneous emails between the grocers’ executives, as well as subsequent testimony of Albertsons executives before the Federal Trade Commission. The so-called “no-poach” and nonsolicitation agreements “harmed workers and blatantly violated antitrust law,” Colorado A.G. Philip Weiser said in a statement.

The stakes of this suit, filed in U.S. District Court in Denver on February 14th, are dramatic. Less than nine months following the conclusion of the King Soopers strike, Kroger announced a plan to acquire Albertsons for $24.6 billion to create the country’s second-largest mega-grocer behind Walmart. The merger is opposed by a broad coalition of labor organizations, independent industry experts, prominent Congressional Democrats from both chambers, and attorneys general from across the country, including Colorado’s Weiser. Yesterday, the Federal Trade Commission announced its own suit to block the deal.

Blunting labor’s pandemic leverage

Like many businesses with large brick-and-mortar footprints, grocers large and small were desperate to hire employees at the time of the strike, 18 months into the pandemic. By late 2021, shifting labor demand and disproportionate frontline fatalities due to Covid helped push the average hourly wage for restaurant and grocery workers past the $15 mark for the first time.

For Kroger workers, the unusual hiring dynamics offered a particular boon. An Economic Roundtable study of 10,000 of the firm’s workers, underwritten by UFCW and published in January 2022, found that "over three-quarters of Kroger workers are food insecure.” The Executive Excesses 2022 report from the Institute for Policy Studies, a progressive think tank, pegged the median pay of Kroger’s workers nationally at just $26,763 in 2021 — 679 times less than the $18 million Kroger chief executive officer Rodney McMullen was paid that year.

As the hours ticked down towards the King Soopers strike, Denver’s CBS4 reported King Soopers stores were already short 2,400 employees in Colorado. “We have brought in 300, 400 people from across the country from some of our sister companies in Kroger,” division president Joe Kelley told the outlet, describing the grocer’s strike preparations. “We have also been hiring temp workers the best we could. You know what the work market looks like.”

The soaring demand for supposedly “unskilled” labor could have created a rare win-win scenario for Colorado King Soopers workers. A strike to force Kroger to offer UFCW Local 7 a better contract would also invite staff-starved competitors like Albertsons — which unlike Kroger, had agreed to extend negotiations between the union and its 100 Safeway stores in Colorado — to lure picketing workers with higher pay and benefits.

Because Albertsons would continue bargaining with UFCW Local 7 for a Safeway contract while Kroger faced a strike over its offer to King Soopers workers, the union was in a position to play the grocers against one another to improve collective bargaining agreements for both workforces. Such a bidding war over labor was in neither company's interest.

A “nefarious bargain”

To protect King Soopers from an Albertsons recruitment raid, and “help Kroger hold the line” and “stay strong” against the UFCW to prevent a bidding war, Weiser alleges that Albersons’ Denver division president Todd Broderick and senior vice president of labor relations Daniel Dosenbach promised Kroger’s vice president of labor relations Jon McPherson that his firm would not poach workers for the duration of the strike.

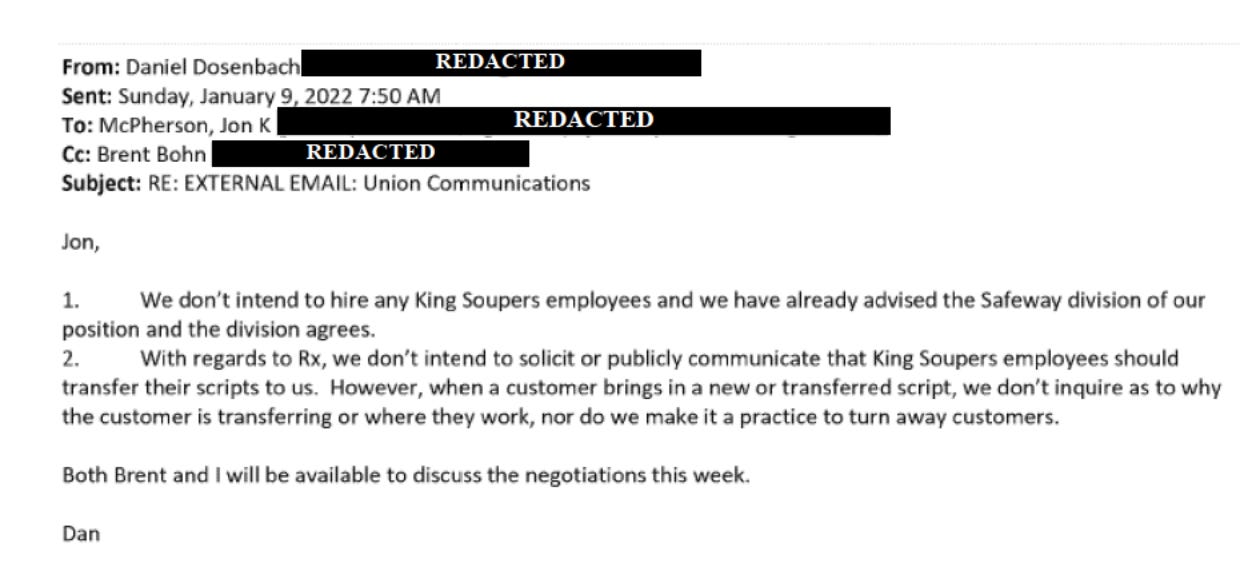

The pair also agreed that Safeway would not encourage King Soopers’ pharmacy customers to move their prescriptions. (For big grocers, pharmacy departments are key because they create customer loyalty and cross-selling opportunities, and King Soopers’ pharmacy technicians were involved in the strike.) Then, they allegedly looped in their respective firms’ top executives about it. The complaint includes a lightly redacted email from Dosenbach to McPherson on January 9th, 2022, with the subject line “Union Communications,” outlining the truce:

A Kroger spokesperson denied the existence of any such arrangements in an emailed statement to Popular Information, calling it “disheartening for Coloradans that General Weiser would mischaracterize the facts.” They declined to elaborate. Albertsons, which reached its own deal with UFCW Local 7 covering 5,400 workers in Colorado and Wyoming in late February 2022, did not respond to Popular Information’s requests for comment.

“The public has a right to know that the leaders of these companies cannot be trusted to do right by their employees or customers,” said Kim Cordova, President of UFCW Local 7 in a statement. A day after the State of Colorado filed suit, the union lodged unfair labor practice charges with the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) based on the allegations in the suit. The NLRB complaint accuses both Albertsons and Kroger of violating federal labor laws with “bad-faith bargaining” and “coercive actions.”

The $24.6-billion elephant in the room

The “nefarious bargain” is not the only illegal activity that Colorado alleges Kroger and Albertsons have undertaken. Colorado's suit alleges the proposed $24.6-billion merger between Kroger and Albertsons is itself illegal. The deal is “precisely the kind of activity that the Colorado antitrust laws were drafted to address,” Colorado’s complaint alleges.

It is not the only entity suing to stop the deal. A week prior to Weiser’s suit, Washington State made its own move to block the controversial tie-up; less than two weeks later, on Monday February 26th, the Federal Trade Commission joined the fight, with eight more states joining in with the regulator’s lawsuit.

The three suits echo concerns from a varied group of opponents to the deal, including the UFCW and The Teamsters (which represent tens of thousands of grocery workers nationally), Congressional Democrats from six states, and 40% of Alaska’s legislature. Kroger and Albertsons say the merger is necessary to compete with Walmart, which controls over 20% of the U.S. grocery market, as well as Costco and Amazon, which acquired Whole Foods in 2017.

“The combine[d] duo would become the latest private sector unionized employer,” wrote grocery analyst Errol Schweizer, the host of industry podcast Checkout Radio and a former Whole Foods Market executive, in a column excoriating the deal shortly after its announcement in October 2022. Along with other independent experts like journalist Benjamin Lorr, author of the 2020 industry exposé The Secret Life of Groceries, Schweizer has argued that the merger will empower the newly combined firm to be “tougher” on unions, slash white-collar jobs, squeeze wholesalers, and close stores that had previously competed with one another in communities that desperately rely on them.

The FTC, announcing its suit, emphasized a dim view of the merger’s labor implications. “A combined Kroger/Albertsons… would gain increased leverage over workers and their unions—to the detriment of workers,” the enforcer alleged in a release.

The FTC’s suit explicitly references the broad strokes of Colorado’s explosive “nefarious bargain” claim (though most of the details are redacted in its complaint.) "Executives from both Respondents acknowledge that the unions’ ability to play them off one another using credible strike threats creates pressure to meet or beat each other’s agreements," the FTC alleges in the filing.

Another “unmitigated failure”?

In a bid to preempt FTC opposition to the deal on antitrust grounds, the companies in September 2023 proposed to divest over 400 stores to a third firm, C&S Wholesale Grocers. In a December 2023 letter requesting the FTC sue to block the deal, Senators Cory Booker (D-NJ), Mazie K. Hirono (D-HI), Bernie Sanders (D-VT), and Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), and Representatives Summer Lee (D-PA) and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) pointed to recent history as evidence that such a “remedy” would fail to ensure competition in the grocery market.

“When Albertsons acquired Safeway, Inc. in 2015, the companies agreed to sell 168 of their stores to four buyers,” the lawmakers wrote. “[T]his effort to preserve competition through structural remedies was an unmitigated failure… In fact, dozens of the locations were sold back to Albertsons, in some cases, for as little as one dollar.”

Kroger insists that history will not repeat itself, claiming C&S is an appropriate competitor to divest the stores, and that the newly merged firm will close no stores as a result of the deal (a notoriously difficult promise to enforce after the fact.) “The merger means workers gain from $1 billion in higher wages, expanded benefits, long-term job security, and a strong unionized workforce,” a Kroger spokesperson told Popular Information in a statement.

Washington and Colorado aren’t buying it. Neither is the FTC. The enforcer, in its announcement of its suit, alleged the grocers’ “inadequate divestiture proposal is a hodgepodge of unconnected stores, banners, brands, and other assets that Kroger’s antitrust lawyers have cobbled together and falls far short of mitigating the lost competition between Kroger and Albertsons.”

As a retired union auto worker, I am in full support of unions. I would not be living now in relative security without my union-won benefits and retirement income.

As far as Walmart goes, I worked in one in my area for about 4 months, and without union protection, I was daily put into situations where physical harm and even death on the job was a distinct possibility.

To clarify, I contracted walking pneumonia while working in the meat department because I had to go into the 0-degree freezer too often. There were pallets of food stacked three high with very little room between them (I almost fell & got trapped with no help coming that I was aware of). If I had I might not be here today because there was no one coming to see where I'd gone and how long I might be unaccounted for.

If there had been a union , I would have addressed this to management and I probably would have if not for the simple reason of knowing that my complaint would have fallen on deaf ears.

On the solution side, why do we have anti-trust laws if we are not going to use them?

The merger will eliminate any competition for grocery prices and inflict much pain on consumers.